Five adjustments would make the EU sustainable finance framework more effective at delivering the desired alignment of incentives

This piece was first published on Bruegel’s website and is available at: How to improve the European Union’s sustainable finance framework

Executive summary

The European Union has sought to steer corporate behaviour to support its climate goals by adopting a large body of rules on sustainable investment, sustainability disclosures and sustainability labelling of financial products, underpinned by a taxonomy of activities considered sustainable. It is unclear, however, if this effort has had significant results. Examination of financial market data and metrics of investment flows towards green and sustainable investment shows up several weaknesses – both contingent and structural – in the EU sustainable finance framework, which could limit its effectiveness in aligning capital flows with climate objectives.

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) is aimed at making the sustainability content of financial products more transparent but rests on a concept of ‘sustainable investment’ that is too broad and loosely defined. Meanwhile, the EU Taxonomy Regulation has not yet become established as the reference framework for corporate bond issuance or sustainable investing. The EU also lacks a coherent framework for transition finance – or investment that is not yet classified as sustainable but that represents progress to greater sustainability – despite this being the market segment to which the largest volumes of investment will need to flow in the short to medium run.

Five adjustments would make the EU sustainable finance framework more effective at delivering the desired alignment of incentives. First, the taxonomy framework should be completed and clarified. Second, the SFDR definition of sustainable investment should be toughened. Third, the neutrality of the framework across capital market instruments, in particular debt versus equity, should be ensured. Fourth, a dedicated framework for transition finance should be developed. Finally, formal sustainable and transition labels for financial products should be introduced.

This approach would make the sustainable finance framework more easily applicable to all kind of companies and all types of capital market instruments, regardless of whether they limit the use of proceeds, and it would be naturally extendable into a framework for transition finance and into a transparent sustainability labelling regime for financial products.

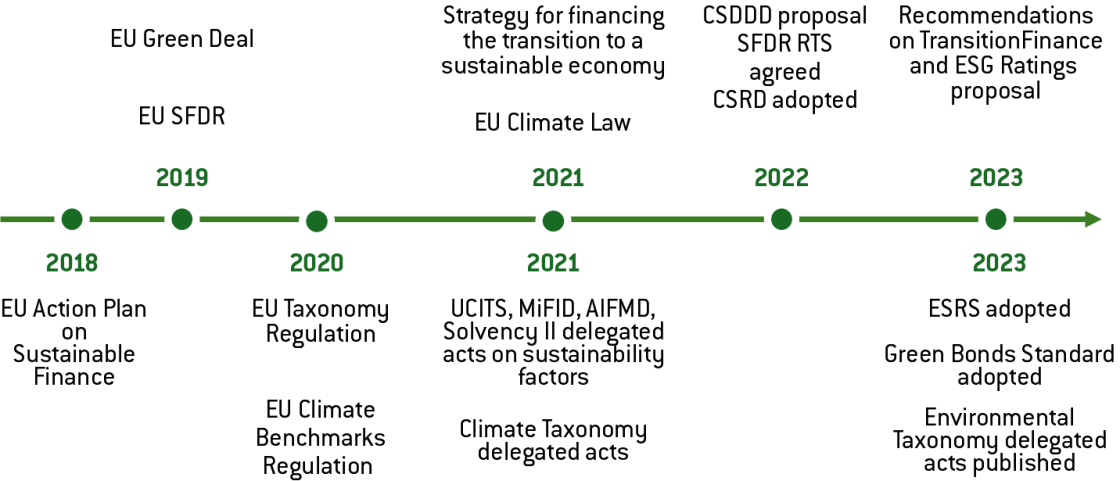

1 A cover-all regulatory umbrella

Over the past seven years, sustainable finance has been the focus of a huge legislative effort in the European Union. The underlying premise has been to put the allocative function of financial markets at the service of climate objectives, including the EU’s goal of a 55 percent greenhouse gas emissions reduction by 2030, compared to 1990. Among a broad series of sustainable finance strategies and plans, including the ‘Strategy for Financing the Transition to a Sustainable Economy’ (Figure 1 and European Commission, 2021), the European Commission proposed regulations aimed both at defining what is meant by ‘sustainability’ and at prescribing sustainability-related disclosures and actions to corporates and financial market participants.

In this Policy Brief, we focus on two of the most consequential of these rules, the Taxonomy Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088), and ask whether they have been successful so far in aligning financial incentives with the EU’s climate policy priorities. We find gaps in the framework, which risk limiting the effectiveness of EU regulation in getting finance to focus increasingly on the activities most needed for the transition to net-zero emissions, and suggest how to plug these gaps. An opportunity to do this is imminent: the European Commission has said it will in late February 2025 propose “streamlining and simplification of sustainability reporting, sustainability due diligence and taxonomy, and create a new category of small mid-caps with adapted requirements” (European Commission, 2025).

Figure 1: Timeline of the EU sustainable finance framework

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission documents. Note: SFDR = Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation; UCITS = Undertakings for Collective Investments in Transferable Securities; MiFID = Market In Financial Instruments Directive; AIFMD = Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive; CSDDD = Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive; CSRD = Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive; ESRS = European Sustainability Reporting Standards.

The landmark Taxonomy Regulation was finalised in 2020 as the world’s only mandatory framework of its type. It sets out criteria to assess the environmental sustainability of economic activities around six objectives: (i) climate-change mitigation, (ii) climate-change adaptation, (iii) sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, (iv) transition to a circular economy, (v) pollution prevention and control, and (vi) restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

According to the Taxonomy Regulation, an activity can be considered environmentally sustainable if: (i) it “contributes substantially” to one or more of the objectives; (ii) it “does not significantly harm” (DNSH) any of the objectives; (iii) it is carried out in accordance with minimum social safeguards; and (iv) it complies with technical screening criteria. Listed companies and large companies (even if non-listed) must disclose the extent to which their activities qualify as environmentally sustainable – ie are ‘taxonomy aligned’). An environmentally sustainable investment is defined as “investment in one or several economic activities that qualify as environmentally sustainable” as per the taxonomy.

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) – applicable since 2021 – introduces disclosure requirements for financial market participants (FMPs) on the sustainability of the investment products they offer in the EU. FMPs must indicate in particular whether products “promote environmental or social characteristics” (so-called Article 8 products) or have “a sustainable investment objective” (Article 9 products). The latter are required to invest only in “sustainable investment”, defined in SFDR as an investment “in an economic activity that (i) contributes to an environmental or social objective; where (ii) the investment does not significantly harm any environmental or social objective; and where (ii) investee companies follow good governance practices”.

The SFDR definition of ‘sustainable investment’ is thus broader than the taxonomy definition of ‘environmentally sustainable investment’, and the European Commission has clarified that sustainable investment under the SFDR can be measured at company level – not just at the level of single activities 1 . Article 8 and Article 9 products must disclose the share of taxonomy-aligned investments they perform, and the share of sustainable investments beyond what is taxonomy-aligned. They can also (but are not required to) commit to allocate a pre-defined minimum share of their assets specifically to taxonomy-aligned investments.

The European Commission’s promised simplification could also affect other laws including the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD, Directive (EU) 2022/2464), which requires companies to publish social and environmental risk reports, and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD, Directive (EU) 2024/1760), which requires companies to assess human rights and environmental risks in their operations and supply chains. This simplification drive should not turn into an opportunity to kill the EU’s past legislative efforts around sustainability, and there should be no compromise on the EU’s climate ambitions nor the means to achieve them 2 . However, there are weaknesses in the sustainable finance framework that have become clear over time and these should be addressed.

2 Re-aligning financial incentives

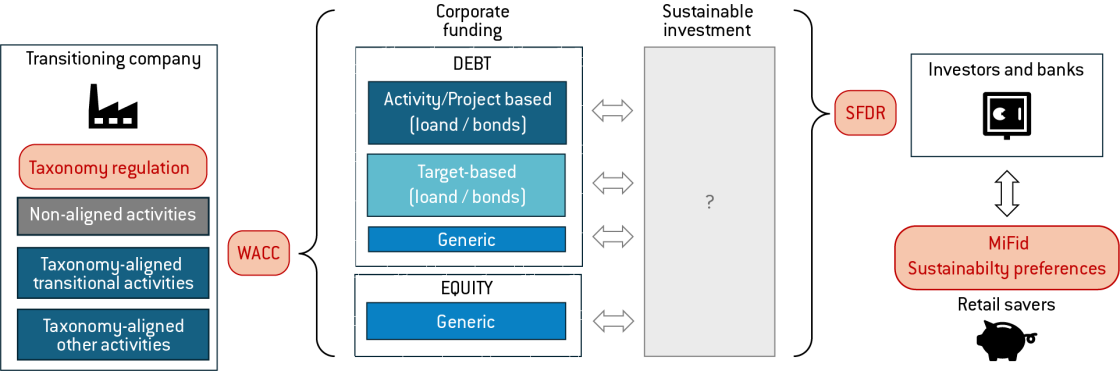

The EU sustainable finance framework’s objective of putting the allocative function of financial markets at the service of climate goals assumes implicitly that regulation can alter the basic incentives that underpin financing decisions in the real economy. Companies typically rely for funding on a combination of debt and equity, and in a world with no sustainability considerations, the appeal of different funding options ultimately depends on how the choice impacts the companies’ weighted average cost of capital (an average rate paid by a firm). When deciding to provide money to companies, FMPs in turn evaluate the risk-return trade-offs of different types of funding.

EU rules aim at altering incentives on the two sides of these funding decisions. The Taxonomy Regulation’s classification system creates an opportunity for companies to issue funding instruments for which the use of proceeds is tied directly to sustainable activities. The most obvious example is green bonds: the use of proceeds must be earmarked for green projects, which can be defined in terms of taxonomy-aligned operating and capital expenses.

If sustainability has a value for investors – because it enhances the investee companies’ performance or reduces risks – then transparency on it is expected to result in a ‘greenium’, ie lower funding costs for companies that are more sustainable (or that turn to funding instruments with embedded sustainability).

However, if FMPs do not intrinsically care about sustainability, increased transparency is unlikely to be enough to alter incentives in their financing decisions. This is where the other components of the sustainable finance framework come into play. Under the so-called MiFID II Directive (2014/65/EU; Markets in Financial Instruments Directive), firms that provide financial advisory or portfolio management services must ask their clients if they have a preference for sustainable investment and must follow those preferences in advisory and allocation 3 .

The combination of sustainability preferences rules with SFDR disclosure requirements aims at ensuring that if there is a preference for sustainability 4 among final consumers of financial products, that preference is made visible to FMPs and FMPs are held accountable against it. The implicit assumption is that greater client demand for sustainable investment plus stricter disclosure requirements can alter incentives for FMPs, making it more appealing for them to invest in companies or instruments that can be disclosed as sustainable investments under SFDR and thus matched with the sustainability preferences of final clients (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A simplified financing decision with sustainability considerations

Source: Bruegel.

If this chain of transparency and accountability is working as intended, two important changes should have been triggered. First, there should be increased issuance of sustainability-labelled corporate funding instruments as companies try to benefit from signalling sustainability in a regulatory environment in which that has higher value. Second, more investment should flow to sustainable financial products as investors seize opportunities that can be matched with clients’ sustainability preferences. In the next section, we assess whether this is happening.

3 Does the EU sustainable finance framework work as intended?

Notwithstanding the European Commission’s stated intentions 5 , financial market data does not yet seem to indicate widespread success of the taxonomy as an anchor for corporate funding strategies, nor as a framework for sustainable investing. This is especially visible when examining two market segments where the taxonomy would in principle find natural application: green bond issuance and investment funds with environmentally sustainable investment objectives.

3.1 The taxonomy is not yet the standard in green bond issuance

Green bonds are funding instruments whose proceeds can only be used to finance ‘green projects’. As the taxonomy outlines a sustainability classification of economic activities, it would seem natural for it to become the reference framework for EU corporate green bond issuance. Examination of the evolution of taxonomy-aligned green bond issuance over time can thus be taken as an indication of whether the Taxonomy Regulation has been successful in driving larger capital flows towards environmentally sustainable economic activities.

Green bonds accounted for 6.5 percent of all bonds issued by EU companies in 2023 (PSF, 2024). Yet only a small share of these were linked to the taxonomy. An end-2024 Bloomberg search returned 2362 outstanding green bonds issued by EU companies since the entry into force of the Taxonomy Regulation. Bloomberg marked 163 of these as funding taxonomy-aligned activities, corresponding to a total amount at issuance of approximately €111 billion.

There is no strong evidence of a structural increase in taxonomy-aligned green bond issuance since 2021 (Table 1). Taxonomy-aligned bonds account annually for up to approximately 10 percent of all EU corporate green bonds. As green bonds in turn represent about 6.5 percent of all EU corporate bonds, taxonomy-aligned bonds constitute an estimated 0.5 percent to 0.7 percent of all EU corporate bond issuance.

Table 1: Green bonds issued by EU companies, as of end-2024

| Number of bonds | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| GBs issued by companies incorporated in the EU | 618 | 547 | 515 | 682 |

| of which, taxonomy-aligned | 13 | 56 | 52 | 42 |

| (2%) | (10%) | (10%) | (6%) | |

| Amount issued (€ billions) | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| GBs issued by companies incorporated in the EU | 852 | 402 | 339 | 399 |

| of which, taxonomy-aligned | 8 | 40 | 34 | 29 |

| (1%) | (10%) | (10%) | (7%) |

Source: Bruegel based on data from Bloomberg. Note: data for 2021, 2022 and 2023 as of 29 September 2024; data for 2024 as of 2 January 2025. Note: taxonomy-aligned bonds are identified as those having a share of taxonomy-aligned use of proceeds greater than 0 percent.

The EU Green Bond Standard (Regulation (EU) 2023/2631) that started to apply at the end of 2024 requires issuers to commit at least 85 percent of proceeds to fund taxonomy-aligned activities, if they want to use the EU Green Bond label. Whether this will succeed in boosting the role of the taxonomy in corporate bond issuance remains to be seen as the standard is voluntary and future uptake will likely hinge on resolution of usability issues that have so far limited the appeal of the taxonomy as a framework for corporate issuance.

As the EU economy remains heavily bank-based, loans predominate in corporate funding, especially for smaller companies. The availability of granular data on the taxonomy-alignment of bank loans is very limited, but anecdotical evidence suggests the volume of taxonomy-linked loans to be small. According to PSF (2024), based on a sample of 4000 SMEs, “over the last two years, 9–10% of SMEs have obtained a green or sustainability-linked loan from a bank”. PSF (2024) also noted that the share of sustainable loans provided by banks to SMEs is estimated to be less than 5 percent to 6 percent of banks’ SME lending portfolios.

3.2 Investors are not embracing the taxonomy in sustainable investing

Another area in which the taxonomy would in principle be expected to find natural application is that of sustainable investment funds. Collective investment funds allow individuals to invest in a variety of assets without buying them directly. Such funds can play an important role in mobilising savings for sustainable investment. Anacki et al (2024) showed that as of June 2024 investment funds accounted for over 13 percent of the total financial assets of European households – probably more, once indirect exposure via pension funds and life insurance is factored in.

The EU asset management industry counts more than 66,000 investment funds, managing €22 trillion in assets (EFAMA, 2024), with approximately 60 percent in the form of UCITS funds 6 , which are easily accessible to retail investors. The SFDR requires investment funds offered in the EU to be classified based on the sustainability commitments in their offering documents (as either ‘Article 6’, ‘Article 8’ or ‘Article 9’). Article 9 funds must have a sustainable investment objective and can invest only in ‘sustainable investments’. These products represent a niche within the broader investment funds market (Figure 3).

Figure 3: SFDR-classified funds out of all investment funds

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg. Note: As of 30 September 2024.

Under the SFDR, Article 9 investment funds must state in their offering documents what share of their assets they commit – as a minimum – to sustainable investments with an environmental objective. Within this share, Article 9 funds must also disclose whether they pre-commit to make any investments in taxonomy-aligned activities.

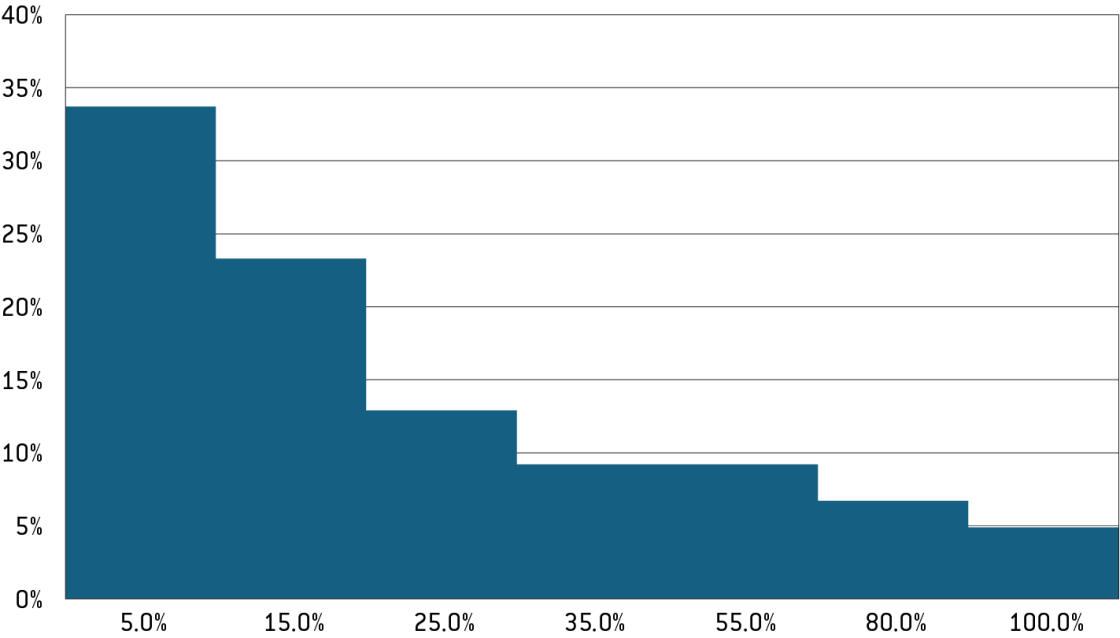

To gauge the impact of the taxonomy in sustainable investing, we look at the extent of taxonomy application by Article 9 funds that commit to environmentally sustainable investments. Out of 973 Article 9 funds (Figure 3), 363 (37 percent) commit to invest at least some of their assets in sustainable investments with an environmental objective. On average, however, these funds only commit to invest 3 percent of their assets in taxonomy-aligned activities, and the median commitment is zero (Figure 4, right panel). Among Article 9 funds that commit to invest more than half of their assets in environmentally sustainable investments, the average taxonomy commitment rises to 5 percent, but the median commitment remains at zero 7 .

Figure 4: Article 9 fund, minimum taxonomy-aligned investment commitment (% total investments)

Source: Bruegel based Bloomberg. Note: As of 17 October 2024.

4 Why is the framework not working as intended?

4.1 Regulatory uncertainty

It is clear that uptake of the taxonomy in corporate issuance has been slow. In part, this is likely explained by legislative delays. The Taxonomy Regulation entered into force in 2020, but criteria for evaluating the alignment of economic activities were defined subsequently. Rules to do this in relation to climate change mitigation and adaptation were finalised in December 2021, then amended in July 2022 (to include energy from gas and nuclear as sustainable). Rules for other objectives were approved in summer 2023. Uncertainty around how to calculate eligible and aligned activities may have acted as a disincentive to a broader uptake of the taxonomy in corporate funding and bond issuance.

Delays and regulatory uncertainty also help explain why the taxonomy so far has not been very successful as a reference framework for sustainable investment in the EU. Originally, the Taxonomy Regulation was supposed to be followed by other sustainability information disclosure requirements for non-financial companies (including listed SMEs) via the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). But taxonomy-related delays led to these being delayed as well, with the first round of CSRD reporting due only in 2025. As a result, FMPs have found themselves facing requirements to report on the sustainability of their investments before non-financial companies were required to disclose information on the sustainability of their activities. This partly explains why FMPs have been cautious in making formal commitments in relation to taxonomy-aligned investments.

Figure 5: EU sustainable finance rules, planned and actual

Source: Bruegel.

4.2 The Taxonomy is not a natural framework for transition finance

Yet, regulatory uncertainty is not the whole story. In the Strategy for Financing the Transition to a Sustainable Economy (European Commission, 2021), the Commission said it wanted to ensure that actors across all sectors will be able to finance their transitions “regardless of their starting point”. Achieving this goal requires scaling-up financing for activities that are already green, but also crucially financing activities that need to transition to sustainability.

The taxonomy is designed to identify what is already sustainable: activities can only be classified as ‘aligned’ or ‘not aligned’. The Taxonomy Regulation tries to cater for the more complex nature of the transition by identifying also what it calls “transition activities” and “enabling activities”, which are deemed to be taxonomy-aligned despite not meeting fully the taxonomy test. By conflating the different concepts of ‘alignment with’ and ‘transition to’ sustainability into a single framework, the regulation creates confusion on what the taxonomy really measures. The binary nature of the taxonomy also makes it challenging to use the framework for transition finance.

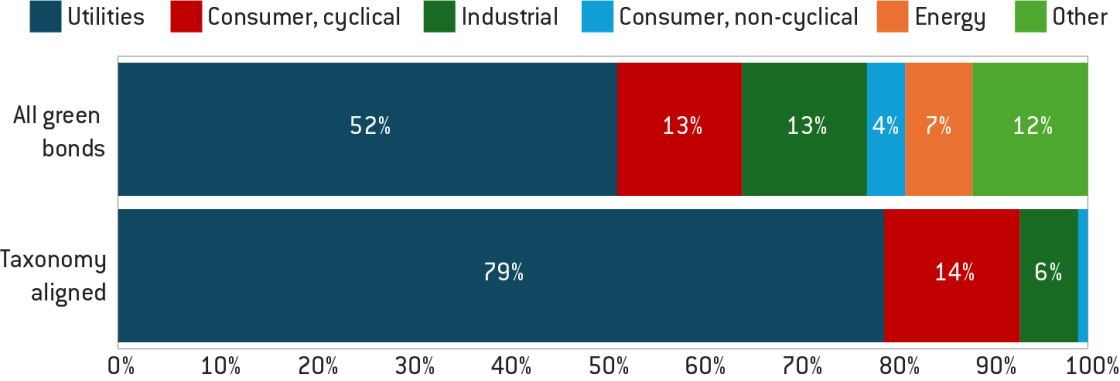

Figure 6: Sector breakdown of taxonomy-aligned EU corporate green bonds

Source: Bruegel based on data from Bloomberg as of 30 September 2024. Note: the chart excludes green bonds issued by companies in the financial sector; if these were included, they would account for 60 percent of all green bonds and 21 percent of all taxonomy-aligned green bonds. The shares of other sectors would be adjusted accordingly.

At present, 79 percent of all taxonomy-aligned green bonds are issued by utilities companies (Figure 6). This share is larger than the share of utilities in broader green-bond issuance (52 percent) and significantly larger than the share of utilities in the EU economy (around 5 percent of output and 3 percent of gross value added (GVA) 8 in 2022). The dominance of utilities in taxonomy-aligned green-bond issuance is due to the relatively fewer requirements on the sector to demonstrate green credentials, compared to sectors – such as industrials – in which showing alignment and meeting the do no significant harm (DNSH) requirement is significantly more complex.

Figure 7 shows gaps between sectors’ taxonomy-eligible and taxonomy-aligned turnover, which can be interpreted as a proxy for the difficulty of demonstrating alignment across different economic activities. The utilities sector is already the most-aligned sector with the largest share of taxonomy-eligible turnover. Of the utilities that have issued taxonomy-aligned green bonds, more than half (53 percent) already have a renewable energy capacity above 80 percent of total capacity 9 . Thus, taxonomy-aligned green bonds so far have been mostly issued by companies that are already green, in a sector in which demonstrating greenness is relatively easy. While this is coherent with the taxonomy being designed to identify sustainable activities, it shows its limits as a framework for transition finance, helping explain why massive volume growth has not yet been seen in this market segment.

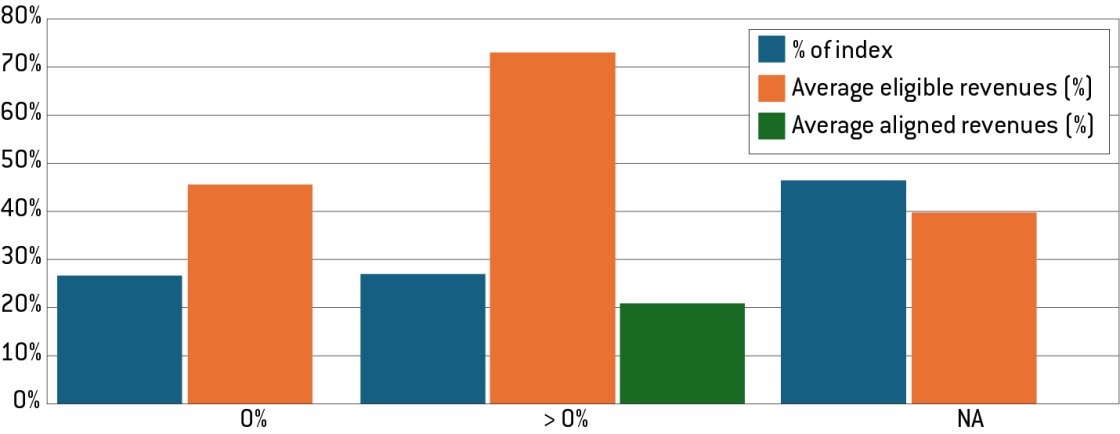

Figure 7: Taxonomy-aligned and taxonomy-eligible turnover by sector (%)

Source: Bruegel based on data from Niewold (2024).

Statistical considerations also play a part. Economic activities are identified in the taxonomy based on the NACE industrial classification, which forms the basis for GDP statistics produced by Eurostat 10 . But it is challenging to match green bonds projects to NACE activities (ICMA, 2022). Green-bond projects often involve numerous activities with individual components relating to different environmental objectives, and NACE codes may sometimes encompass multiple activities, while in other cases corporate activities may have no reference NACE, making it impossible to classify projects for taxonomy purposes 11 . While an alternate NACE mapping has been published, usability issues persist (ICMA, 2023).

4.3 Taxonomy-aligned investing trades off low diversification

Regulatory uncertainty helps explain the scepticism of financial market participants (FMPs) about committing to taxonomy-aligned investment (section 4.1). As long as corporates remain reluctant to embrace the taxonomy, investors will likely remain cautious on their taxonomy commitments. But there are other reasons why the framework may remain unappealing for investors in the immediate future.

Figure 8: Taxonomy-eligible and aligned revenues of Euro STOXX 600 (% companies)

Source: Bruegel based on data from Bloomberg, as of November 2024. Note: N.A. indicates companies for which the share of taxonomy-aligned revenues is not known.

The real economy is currently not highly aligned with the EU taxonomy. The average taxonomy revenue alignment of companies in the Euro STOXX 600 Index – which represents 90 percent of European market capitalisation – is a mere 10.5 percent. Only 27 percent of these companies have at least some taxonomy-aligned revenues (Figure 8). Among these, average alignment is 21 percent. Accordingly, the ex-post exposure to taxonomy-aligned activities for most Article 9 funds is also very low – 15 percent or less of total revenues at the end of 2024 (Figure 9).

Almost half the companies in the Euro STOXX Index derive 80 percent or more of their revenues from activities that are eligible under the taxonomy, so the average alignment across the European stock market will increase as these companies transition. But that will take time. In the meantime, investors aiming to achieve high ex-post taxonomy alignment in their portfolios are left to pick from a small set and must accept high levels of concentration 12 .

Figure 9: Average taxonomy-aligned % of revenues for Article 9 portfolio companies

Source: Bruegel based on data from Bloomberg, as of 4 November 2024.

For investors, this is a problem. Less diversification means more risk. This trade-off became painfully evident in 2023. As central banks embarked on fast rate hikes, renewable energy companies faced an unanticipated spike in funding costs and were forced to undertake sizeable impairments. As a result, the iShares Global Clean Energy UCITS ETF, whose portfolio has an average taxonomy-alignment of 66 percent, recorded a return of negative 23 percent for 2023. The iShares MSCI World Paris-Aligned Climate UCITS ETF, which tracks an index that is prevented from investing companies with high fossil fuel exposure but has only 17 percent average taxonomy-alignment, was up 21 percent in the same period. Until a higher degree of taxonomy-alignment is reached across the real economy, this concentration risk will likely remain a disincentive for investors to commit to substantial taxonomy-aligned investment.

4.4 Reaching taxonomy alignment is harder for equity investors than fixed-income investors

The problems we highlighted in the previous sections are especially problematic for equity investors. Fixed-income investors could in theory reach a high level of taxonomy alignment in their portfolios by selecting taxonomy-aligned bonds, even if these are issued by companies with low or no taxonomy alignment. As long as the proceeds from the bonds are used for taxonomy-aligned activities, the entire bond investment would be considered aligned and would automatically qualify as sustainable investment under the SFDR. Equity investors do not have this option, because equity is a general funding instrument.

As such, the taxonomy-alignment of a listed equity portfolio will inevitably be tied to the overall alignment of the investees’ business. Table 2 shows how the same portfolio can yield different taxonomy alignment when the investment is in the form of listed equity versus green bonds 13 , and how an investment in an EU green bond issued by a company that has only a minimal share of its revenues or capex aligned with the taxonomy is worth ‘more’ – in sustainability terms – than an equity investment in a company that has a high level of (but not full) taxonomy alignment. This seems to be a paradoxical result.

This helps highlight an implicit assumption in the sustainable finance framework: in the early stages of transition – when companies are not yet highly taxonomy-aligned – sustainability-minded investors should only invest via instruments that segregate the use of proceeds for taxonomy-aligned activities, if they want their investment to be deemed ‘sustainable’. Only in later stages of the transition, when the overall taxonomy-alignment at company level has increased, will investing in general funding instruments such as equity qualify as sustainable investment 14 .

Table 2: Example of portfolio taxonomy-alignment calculations (equity vs green debt)

| Portfolio | Company taxonomy-aligned revenues (%) | Portfolio weight (% total investment) |

| Company A | 80% | 25% |

| Company B | 5% | 25% |

| Company C | 20% | 25% |

| Company D | 40% | 25% |

| Green bond portfolio alignment | Σi (portfolio weighti* bond alignmenti)(25%*100%) +(25%*100%) +(25%*100%) +(25%*100%) = 100% | |

| Listed equity portfolio alignment | Σi (portfolio weighti* company alignmenti )(25%*80%) +(25%*5%) +(25%*20%) +(25%*40%) = 36% | |

Source: Bruegel.

Yet, the SFDR definition of ‘sustainable investment’ remains vague and stops short of setting minimum requirements for what a ‘significant contribution’ is or for when an investment poses ‘significant harm’. FMPs must carry out their own assessments and disclose their assumptions, which can result in confusion – for example, that asset managers had been led “to adopt different approaches to the calculation of sustainable investment exposure and taxonomy alignment, rendering it impossible to compare products directly” 15 . In a European Commission public consultation on the SFDR in 2023, a majority (62 percent) of respondents argued that the regulation has not strengthened protection for end investors or made it easier for them to compare products with sustainability claims 16 .

The problem with the approach described above is twofold. The activity-level focus of the taxonomy risks introducing an implicit sustainability hierarchy across funding instruments, in which it is easier for fixed-income portfolios than for equity portfolios to achieve a high taxonomy-alignment (and meet sustainable investment requirements under the SFDR). This in turn may bias corporate funding strategies towards debt, where use-of-proceeds rules can be easily embedded. But in practice, debt and equity capital are both needed and serve different purposes. Equity capital bears higher risk and is essential to finance the radical innovation in which Europe invests too little. By making it inherently harder for equity investors to demonstrate the sustainability of their portfolios, the current framework risks dissuading sustainability-minded investors from providing equity capital to companies that need to transition.

4.5 The EU lacks a standard for target-based transition finance

One market segment that has seen a sizeable increase over the past few years is that of sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) or loans. The funds raised with SLBs can be used for any purpose (in that they are general funding instruments) but the cost of that funding increases if the company misses some pre-determined sustainability targets.

These instruments can be a powerful driver of the transition, but their effectiveness depends on the level of ambition of their targets and the size of the penalty for missing them. Between 2021 and 2024, companies incorporated in the EU issued a total of €118 billion in SLBs, 62 percent of which had at least one greenhouse-gas emission reduction target. For the majority of greenhouse-gas-linked SLBs, targets covered only part of the companies’ emissions and the penalty for missing targets tended to be small (Merler, 2024). In a still non-standardised and relatively opaque market segment, the risk is significant that companies will lower the ambition of SLBs targets to reduce the likelihood of being caught off guard. Europe is the largest market for behaviour-based debt instruments and the most advanced jurisdiction when it comes to regulating corporate transition targets, so it should reap the potential of an efficient SLB market by introducing an EU standard for SLBs, similarly to what it did with the EU Green Bond Standard.

4.6 It is unclear whether transition finance qualifies as sustainable investment

In June 2023, the Commission published a recommendation on “facilitating finance for the transition to a sustainable economy”, in which it stated that transition finance should be understood as “financing of climate and environmental performance improvements to transition towards a sustainable economy, at a pace that is compatible with the climate and environmental objectives of the EU” (European Commission, 2023). The recommendation also listed four examples of investments compatible with this definition:

a) Investments in portfolios tracking EU climate benchmarks;

b) Investments in taxonomy-aligned economic activities;

c) Investments in undertakings or economic activities with a credible transition plan at the level of the undertaking or at activity level;

d) Investments in undertakings or economic activities with credible science-based targets, where proportionate, which are supported by information ensuring integrity, transparency, and accountability.

The recommendation stated that “sustainable finance is about financing both what is already environment-friendly and what is transitioning to such performance level over time”. This seems to suggest that transition finance is to be understood as part of sustainable investment, not separate from it. But EU regulation does not treat the four types of transition finance listed in the recommendation in the same way, when it comes to assessing whether they qualify as sustainable investment under the SFDR.

While investments under (a) and (b) are automatically considered to be ‘sustainable investment’, (c) and (d) are not. When it comes to transition-plan and target-based investments – points (c) and (d) in the recommendation – EU regulation is unclear. The European Commission has suggested that investments in companies that have climate targets may not qualify as sustainable investment solely by virtue of having such targets, but FMPs need to also demonstrate that the transitioning assets meet the SFDR DNSH test already at the time of investment 17 . This might be difficult for companies at an early stage of transition.

5 How to fix it

Adjustments can be made to the EU sustainable finance framework to make it more effective at delivering the desired alignment of incentives. At the core of our recommendations is therefore the creation of a clear, transparent and dedicated framework for transition finance – which is currently not properly defined in the EU legal framework.

5.1 Complete and clarify the taxonomy framework

As discussed in section 4.2, the binary nature of the taxonomy (sustainable/not sustainable) makes it complex to use the taxonomy as a tool for transition finance, likely explaining why the taxonomy does not yet appear to be widely used by corporates in bond issuances, or by investors for sustainable investing. European Commission (2023) stressed that the taxonomy should be used not just as a reporting tool, but as a planning and strategy framework. For this to happen, the taxonomy should be completed to add all economic activities that can contribute, even marginally, to environmental sustainability. In addition, introducing a ‘traffic light’ structure, with an amber category for transitional activities and a red category for harmful ones, would increase transparency and boost the usability of the taxonomy as a transition-finance framework (High Level Group, 2023).

5.2 Toughen the SFDR definition of sustainable investment

As highlighted in section 1, confusion persists on what ‘sustainable investment’ means under EU law. The Taxonomy Regulation and SFDR define it differently, prompting ESMA (2023a) to issue a clarification. Yet, the reasons for concern over the definition remain unaddressed – and uncertainty is problematic for both companies and FMPs in terms of their own sustainability disclosures and planning, as well as for the final consumers of financial products.

The Commission has outlined two types of investment that qualify automatically as sustainable investments under SFDR: passive funds tracking EU climate benchmarks and investments in taxonomy-aligned activities. But the regulation sets no minimum criteria for how sustainability should be evaluated in other cases.

The SFDR definition of sustainable investment should thus be reviewed. The concepts of ‘substantial contribution’ and ‘significant harm’ should be made prescriptive (as suggested by eg ESAs, 2024). In 2020, the EU introduced climate benchmarks, which are subject to environmental investment restrictions. The EU Paris Aligned Benchmarks (PABs) must align the carbon emissions of their underlying portfolio with the Paris Agreement targets, and are subject to environmental investment policy restrictions. In particular, PABs cannot include in their underlying portfolios companies that are involved in specific social and/or environmentally harmful activities (eg fossil fuels). This approach should be incorporated in the definition of ‘sustainable investment’ under SFDR. To be considered ‘sustainable’ under SFDR, an investment should need to meet the same environmental investment restrictions that are applicable to the EU PABs. For investments that do not meet PAB criteria but that meet the less-stringent Climate Transition Benchmarks criteria, a new category labelled ‘transitional investments’ should be created within the SFDR framework.

Guidance should also be provided on how the SFDR ‘contribution’ to sustainability objectives should be defined and quantified. ESAs (2024) leaned towards relying on the EU taxonomy as the default framework for assessing this contribution to taxonomy-eligible activities, and stated that other non-specified “appropriate sustainability metrics and minimum requirements” should be used for activities that are not taxonomy-eligible. However, as long as the taxonomy remains incomplete and the usability issues we have described remain unaddressed, this two-tier approach risks replicating the inconsistencies we have highlighted.

5.3 Ensure neutrality across capital-market instruments

As discussed in section 4.4, the mismatch between the definition of sustainable investment under SFDR and under the taxonomy risks introducing an implicit bias against equity capital – because the taxonomy alignment of an equity investment necessarily depends on the entity-level taxonomy alignment of the investee company, rather than on the alignment of specific projects being funded. To be truly effective, the EU sustainable-finance framework should be applicable in a neutral way across all capital-market instruments.

One option to achieve this would be to rescale the taxonomy-alignment of green bonds by a measure of the overall taxonomy alignment of the company, in order to avoid the paradox that we describe in section 4.4 and to preserve neutrality of the framework across capital market instruments. However, this would completely defeat the purpose of green bonds, which is to allow companies to raise funding at a discount by earmarking the funds for green projects.

An alternative could be to assess sustainability using a top-down/entity-level approach while clarifying the difference between sustainability and transition. To determine whether providing funding (of whatever kind) to a company qualifies as sustainable investment, the starting point could be be an evaluation of whether the company’s revenues and/or capex – taxonomy-eligible or not – align with the environmental objectives of the European Green Deal. A model for this could be the mapping framework being developed by the PSF (2024b) to evaluate sustainable capital flows for which taxonomy alignment cannot be established.

If that option is chosen, then a Green Deal alignment threshold could be set – out of total company revenues and/or capex – to determine whether investing in a company would meet the substantial contribution requirement. If the company clears the threshold and meets the stricter PAB-aligned minimum SFDR exclusions we recommend in section 5.2, then any type of investment in the company, including via general debt or equity, should be fully eligible as sustainable investment. If the company does not clear the threshold, then only investments by means of use-of-proceeds instruments, or Paris-aligned sustainability-linked (see below) instruments, should be deemed sustainable investment.

This approach would help solve a number of issues. First, it would be immediately applicable to all companies – including those operating in activities that are not yet eligible under the taxonomy. Second, it would be applicable to non-EU companies – which are not bound to report taxonomy-alignment but report revenue breakdowns that can be used for this assessment. Third, it would be neutral across capital-market instruments, regardless of whether or not they limit the use of proceeds, because it would be based on an assessment of sustainability at the company level. Lastly, it could be extended easily into a framework that more clearly and transparently caters for both transition finance and sustainable finance.

5.4 Develop a dedicated framework for transition finance

While scaling-up finance for already sustainable activities is important to meet EU climate goals, financing the transition of what can become sustainable is equally important. Yet, the EU has neither a proper legal definition of transition finance nor a dedicated framework. The 2023 Commission recommendation on transition finance stated that “sustainable finance is about financing both what is already environment-friendly and what is transitioning to such performance level over time” (European Commission, 2023). This seems to suggest that transition finance is to be understood as part of sustainable investment, not separate from it. But, as discussed in section 4.6, there are inconsistencies and confusion across EU regulation on this point, and they should be reconciled.

The process that we propose above would make it easier to frame transition finance more coherently across EU law. Companies that are not yet at a stage of clearing the sustainable investment threshold could be evaluated for whether they qualify as transitioning by looking at whether they have credible science-based transition plans and targets (in line with CSRD and CSDDD requirements). Investing in those companies would then qualify as “transition investment”, as these companies would be on a science-based path towards sustainability. This approach would be applicable neutrally across capital market instruments, and would have the benefit of incentivising companies to set science-based climate transition targets as a way to signal a credible transition, potentially benefitting from a transition premium.

The EU should also consider pushing for the concepts of ‘sustainability’ and ‘transition’ to be more properly reflected in the sustainability ratings (or ESG ratings) sold in the EU. ESG ratings are used by most FMPs as a synthetic measure of corporate sustainability, but well-known flaws exist in terms of how these ratings are built, which makes them a poor proxy for corporate sustainability (Esposito and Merler, 2024) 18 . EU regulation strongly embeds in reporting obligations the concept of double materiality – ie the idea of measuring both the impact of a company’s products and operations on the environment and society, and the impact of environmental and social factors on the company’s financials. Many ESG ratings providers, however, do not apply a double-materiality approach to their ratings. In our view, ESG ratings providers – while retaining full ownership of their methodologies – should be required to use a double-materiality approach for ESG ratings sold in Europe. This would align the ratings with the approach to corporate sustainability that the EU is taking in the CSRD and the SFDR.

Lastly, the EU framework for transition finance should include a dedicated EU standard for sustainability-linked funding instruments, similarly to the EU Green Bond Standard. As discussed in section 4.5, Europe is the largest market for behaviour-based debt instruments and the most advanced jurisdiction when it comes to regulating corporate transition targets, so it should act to reap the potential of an efficient and ambitious SLB market. Whether these instruments should be qualified as ‘sustainable’ or ‘transition’ investment could be linked to the level of ambition of their targets, thus creating an incentive for companies to set ambitous goals. For example, SLBs linked to Paris-aligned and validated science-based targets (ie the ‘gold standard’ in terms of target setting) could be considered sustainable, although a provision should be included under which the bonds would lose sustainable status if targets are missed.

5.5 Introduce formal sustainable and transition-finance labels

Clearer definitions should be extended into a transparent labelling system for financial products. SFDR Articles 8 and 9 categories were not supposed to be used as sustainability labels – but in practice they have been. We recommend creating instead two proper labels, for ‘sustainable’ and ‘transition’ financial products respectively.

Products aiming for the ‘sustainable’ label should invest in assets that are already sustainable. To be deemed sustainable, individual investments should meet the revised prescriptive DNSH under the SFDR that we call for in section 5.2, and the substantial contributions threshold proposed in section 5.3. ESAs (2024) proposed that for environmentally sustainable products, the threshold should be based on taxonomy-aligned investments, but we would caution against this approach. Reaching a high degree of ex-post taxonomy alignment at present requires accepting low diversification (section 4.3), and this is likely one of the reasons for the very low observed ex-ante commitments to taxonomy-aligned investing. As long as this remains the case, and the taxonomy remains incomplete, there could be value in considering a broader definition of sustainability, for example as proposed in section 5.3.

Investment products aiming for the ‘transition’ label should be able to invest in assets that do not yet clear the sustainability threshold, but for which there is a demonstrated science-based and credible path to sustainability. If a red category is added to the taxonomy, transitional products could also be required to publish and pursue a transparent phase-out plan for exposure to red activities within their portfolio (eg via engagement).

ESAs (2024) seemed to suggest these two categories should be mutually exclusive but this does not have to be the case. As the whole economy transitions, companies in the portfolios of transition investment products should be expected to become progressively more sustainable over time, and it would be natural for the portion of the portfolio that clears the sustainability threshold to increase as a consequence. There would seem to be no obvious reason to ‘force’ transition products to divest from companies that have switched from transitioning to sustainable. Sustainable and transition investments should rather be allowed to coexist within the portfolios of transition products, as long as transparent disclosure rules are set around respective shares in the portfolio.

6 Conclusion

Over the past decade, the EU has set ambitious climate goals, which will require massive investment. Sustainable finance must play a major role and much regulatory activity has gone into building a framework to reorient capital flows in line with climate goals.

However, this effort is not yet delivering the desired results. The core pillar of the EU sustainable finance framework – the taxonomy – has not established itself as a reference framework in corporate funding or sustainable investing. While legislative uncertainty has played a role in this, and takeup of the taxonomy may improve in the future, there are also structural reasons to be sceptical that this will happen. The most compelling of these is the lack of a coherent EU framework for transition finance.

The EU sustainable finance framework should be made more easily operational and more effective at delivering the desired alignment of incentives across the real economy and the financial sector. The changes we propose in this Policy Brief would be instrumental in achieving that result. The framework we propose would have the benefit of being applicable to all companies, but most importantly, it would be neutrally applicable across all capital-market instruments and easily extendable into a framework for transition finance and a transparent labelling regime.

References

Anacki, M., A. Aragonés, G. Calussi and H. Olsson (2024) ‘Exploring the investment funds households own’, ECB Data Blog, 17 September, European Central Bank, available at https://data.ecb.europa.eu/blog/blog-posts/exploring-investment-funds-households-own

Anderson A. and D.T. Robinson (2022) ‘Financial literacy in the age of green investment’, Review of Finance 26(6): 1551-1584, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfab031

Bauer R., T. Ruof and P. Smeets (2021) ‘Get real! Individuals prefer more sustainable investments’, The Review of Financial Studies 34(8): 3976-4043, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhab037

EFAMA (2024) ‘Trends in the European Investment Funds Industry in the second quarter of 2024’, Quarterly Statistical Release 98, European Fund and Asset Management Association, available at https://www.efama.org/sites/default/files/quarterly-statistical-release-q2-2024.pdf

Engler, D., G. Gutsche and P. Smeets (2024) ‘Why do Investors Pay Higher Fees for Sustainable Investments? An Experiment in Five European Countries’, mimeo, available at https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4379189

ESAs (2024a) ‘Consolidated questions and answers (Q&A) on the SFDR (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) and the SFDR Delegated Regulation (Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/1288)’, European Supervisory Authorities, available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-05/JC_2023_18_-_Consolidated_JC_SFDR_QAs.pdf

ESAs (2024b) ‘Joint ESAs Opinion on the assessment of the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)’, JC 2024 06, available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2024-06/JC_2024_06_Joint_ESAs_Opinion_on_SFDR.pdf

ESMA (2022) ‘Answers to questions on the interpretation of Regulation (EU) 2019/2088, submitted by the European Supervisory Authorities on 9 September 2022’, available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-04/Answers_to_questions_on_the_interpretation_of_Regulation_%28EU%29_20192088.PDF

ESMA (2023a) ‘Concepts of sustainable investments and environmentally sustainable activities in the EU Sustainable Finance framework’, ESMA30-379-2279, available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-11/ESMA30-379-2279_Note_Sustainable_investments_SFDR.pdf

ESMA (2023b) ‘Do No Significant Harm’ definitions and criteria across the EU Sustainable Finance framework’, ESMA30-379-2281, available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-11/ESMA30-379-2281_Note_DNSH_definitions_and_criteria_across_the_EU_Sustainable_Finance_framework.pdf

Esposito, I. and S. Merler (2024) ‘The EU ESG Ratings Regulation: A Game Changer?’ ESG & Policy Research, 23 February, Algebris Investments, available at https://www.algebris.com/esg-policy-research/the-green-leaf-the-eu-esg-ratings-regulation-a-game-changer/

European Commission (2021) ‘Strategy for Financing the Transition to a Sustainable Economy’, COM(2021) 390 final, available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52021DC0390

European Commission (2023) ‘Commission Recommendation 2023/1425 on facilitating finance for the transition to a sustainable economy’, C/2023/3844, available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023H1425

European Commission (2025) ‘Commission work programme 2025; Moving forward together: A Bolder, Simpler, Faster Union’, COM(2025) 45 final, available at https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/f80922dd-932d-4c4a-a18c-d800837fbb23_en

Gutsche, G., H. Wetzel and A. Ziegler (2023) ‘Determinants of Individual Sustainable Investment Behaviour – A Framed Field Experiment’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 209: 491–508, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2023.03.016

Heeb, F., J. Kölbel, S. Ramelli and A. Vasilieva (2023) ‘Green Investing and Political Behavior’, Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper 23-46, available at https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4484166

High Level Group (2023) Transition finance in the EU: is the framework fit for purpose? High Level Groups on EU Policy Innovation, available at https://www.highlevelgroup.eu/single-post/transition-finance-in-the-eu-is-the-framework-fit-for-purpose

ICMA (2022) Ensuring the usability of the EU Taxonomy, International Capital Market Association, available at https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/GreenSocialSustainabilityDb/Ensuring-the-Usability-of-the-EU-Taxonomy-and-Ensuring-the-Usability-of-the-EU-Taxonomy-February-2022.pdf

ICMA (2023) ‘Update on the recent provisional agreement on the EU GBS’, International Capital Market Association, 5 April, available at https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/Responses/ICMA-update-on-the-recent-EU-GBS-Provisional-Agreement-April-2023-050423.pdf

IPSF (2022) Common Ground Taxonomy – Climate Change Mitigation, Instruction Report, International Platform on Sustainable Finance, available at https://finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-12/211104-ipsf-common-ground-taxonomy-instruction-report-2021_en.pdf

Kölber, J. and C. Weder (2024) Sustainability preference elicitation under MiFID II – a market survey, Center for Financial Services Innovation, University of St. Gallen, available at https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmgsites/ch/pdf/kpmg-ch-sustainability-preference-elicitation-report.pdf

Mahmood, R., S. Subramanian and S. Guo (2023) Funds and the State of European Sustainable Finance, MSCI ESG Research, available at https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/f89743d6-037f-bb73-1750-d606482224b0

Merler, S. (2024) ‘An Italian utility company missed their emissions target: what does it mean for the Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) market?’ Market Views, 2 May, Algebris Investments, available at https://www.algebris.com/market-views/an-italian-utility-company-missed-their-emission-target-what-does-it-mean-for-the-sustainability-linked-bonds-slb-market/

Niewold, J. (2024) ‘How to Navigate the EU Taxonomy’, EY, 10 September, available at https://www.ey.com/en_gl/insights/assurance/eu-taxonomy-report

OECD (2022) OECD Guidance on Transition Finance, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, available at https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/10/oecd-guidance-on-transition-finance_ac701a44/7c68a1ee-en.pdf

PSF (2024a) A Compendium of Market Practices, Platform on Sustainable Finance, available at https://finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2024-01/240129-sf-platform-report-market-practices-compendium-report_en.pdf

PSF (2024b) Monitoring Capital Flows to Sustainable Investment: Intermediate Report, Platform on Sustainable Finance, available at https://finance.ec.europa.eu/document/download/5dfafa22-ebdf-43d8-88bb-f48c44ecd28e_en

TEG (2019) Taxonomy pack for feedback and workshops invitations, Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance, available at https://finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-01/sustainable-finance-taxonomy-feedback-and-workshops_en.pdf

Silvia Merler, Head of ESG & Policy Research (Algebris Investments)