This piece was first published on Bruegel’s website and is available at: Sustainability rules are not a block on EU defence financing, but reputational fears are

The European Commission’s ReArm Europe plan, published on 5 March, aims to trigger €800 billion in defence investments over four years. European Union money would be limited to €150 billion in the form of loans and the plan hinges on increasing military spending by national governments and “mobilising private capital” 1 But without clarification on the acceptability of and need for defence investment within the EU sustainable finance framework, the private sector is unlikely to meet these expectations.

Regulatory constraints are flexible

The EU’s sustainable finance rules do not place overarching restrictions on defence investment, but there are restrictions on financing companies involved in the production of ‘controversial weapons’ – which are defined as “those referred to in international treaties and conventions, United Nations principles and, where applicable, national legislation” (Regulation (EU) 2020/1818).

The financial industry understands controversial weapons to be anti-personnel landmines, cluster munitions and sub-munitions, chemical and biological weapons, non-detectable fragments, white phosphorous, blinding laser weapons and depleted uranium (MSCI, 2024a). Nuclear weapons, despite their potential for mass destruction, are not typically part of the list.

Companies that derive revenues from controversial weapons cannot be included in EU Paris-aligned benchmarks and Climate Transition Benchmarks 2 – broad market indices that can be considered aligned with the goal of a net-zero economy. Nor would they be eligible for inclusion in portfolios of products tracking those benchmarks. In lines with rules published in May 2024 by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA, 2024) for collective investment funds, funds with “sustainability-related terms” (such as ‘sustainable’, ‘sustainability’ and similar) in their names also would not be allowed to invest in these companies.

Involvement in controversial weapons also matters for the determination of whether companies are aligned with the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities – a categorisation to determine if economic activities are in line with the EU’s 2050 net-zero goal 3 . To be taxonomy-aligned, an activity must meet minimum social safeguards, which, according to Commission guidance, would preclude exposure to controversial weapons 4 .

Consequently, providers of environmental, social and governance (ESG) data typically consider companies non-taxonomy-aligned if they are involved in controversial weapons (eg MSCI, 2024b). This matters both for investors, who under EU sustainable finance rules must report the taxonomy-alignment of their investments, and for banks. The green asset ratio EU banks must disclose from 2024 is in fact defined as a bank’s share of taxonomy-aligned assets out of total assets. The ratio would drop if banks were to significantly increase investment in companies involved in controversial weapons.

At the end of 2023, 74 percent of all climate-transition fund assets globally (for a total of $155 billion in assets) were tracking an EU climate benchmark and would thus be restricted from investing in companies involved in controversial weapons 5 . In relation to fund name rules, up to 500 funds might need to rename or divest from companies involved in controversial weapons (Willman et al, 2024).

However, regulatory constraints alone are unlikely to deter investment in EU defence companies, because they are at present not widely involved in ‘controversial weapons’ as defined in EU law.

Reputational constraints are tight

When it comes to financing defence, non-regulatory constraints introduced voluntarily by financial-market participants out of reputational concerns are likely to matter more than regulatory constraints. Draghi (2024) argued that access to financing for EU defence companies is partly hindered by the way financial institutions interpret EU sustainable finance rules.

This is visible when looking at collective investment funds, which play a major role in mobilising savings for investment. The EU asset management industry manages €23 trillion in assets (EAFMA, 2024), 65 percent of which is in the form of Undertaking for Collective Investment in Traded Securities (UCITS) funds, which are easily accessible to retail investors.

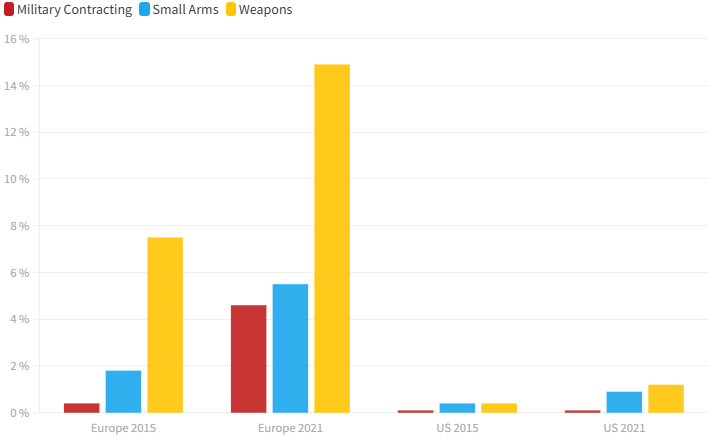

The penetration of investment restrictions targeting the defence sector increased massively across European investment funds between 2015 and 2021 (Figure 1). As of 2021, 14 percent of all retail assets under management in Europe was subject to some restriction on weapons-related investments – a trend not seen in the United States.

Source: Jones, D. and L. Templeman (2022) based on Morningstar Direct. Note: averages across exchange-traded funds and mutual funds.

Going nuclear

Though not required by EU regulation, many collective investment funds do apply tight self-imposed restrictions on investment in nuclear weapons producers.

Under the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR, Regulation (EU) 2019/2088), collective investment funds offered in the EU must be classified either as ‘Article 6’ (products that make no sustainability claims and have no ESG integration in the investment process, other than a basic assessment of sustainability risks), ‘Article 8’ (sometimes referred to as ‘light green’, they integrate ESG considerations into the investment process but stop short of committing to sustainable investment only) or ‘Article 9’ , products that can only carry out sustainable investments.

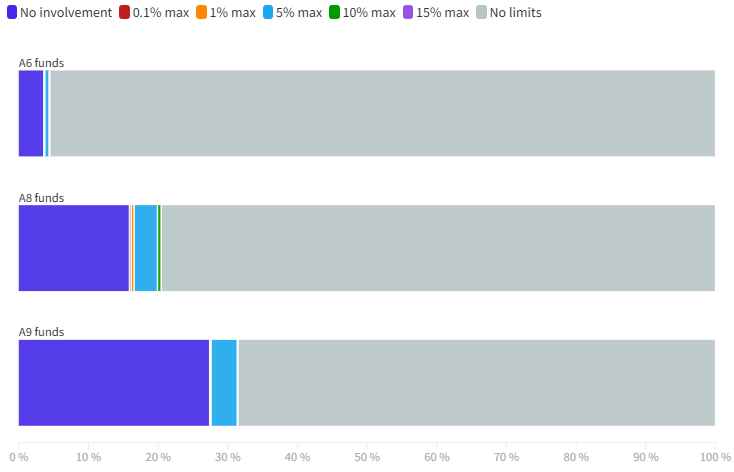

Restrictions on investing in defence are unsurprisingly tightest for Article 9 funds, but they are also present across Article 8 and Article 6 funds. Some 28 percent of Article 9 funds, 16 percent of Article 8 funds and 4 percent of Article 6 funds have zero tolerance for nuclear-weapons involvement (Figure 2). An extra 3 percent to 4 percent of Article 9 and Article 8 funds instead restrict investment in companies that derive more than 1 percent to 5 percent of their revenues from these weapons.

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg data (as of 6 March 2025). Note: the figure shows maximum share of revenues that investees can derive from nuclear weapons and remain eligible for investment, based on the funds’ policies.

On the banking side, measures taken by the European Investment Bank (EIB) show how these issues are being dealt with in practice. The EIB Group is supposed to deploy financial instruments to address prevailing market failures but excluded the defence industry – which was structurally under-invested – until May 2024, despite the ongoing war in Ukraine. In May 2024, the EIB waived a requirement that dual-use projects eligible for financing should derive more than 50 percent of their expected revenues from civilian use.

This stance had a spillover effect on other public banks and a powerful signalling effect on the wider financial sector. Of the 27 EU banks currently included in the EURO STOXX Banks Index 6 , all but three have policies barring them from financing companies involved in controversial weapons, and in most cases these policies encompass nuclear weapons, with no exceptions for EU companies and/or countries.

What can be done to facilitate private defence funding?

Following the announcement of the ReArm Europe plan, the EIB is lifting its self-imposed limit on defence funding and broadening the scope of defence projects eligible for receiving EIB funding 7 . But it will likely take longer for EU commercial banks and investors to change the defence-funding policies they have had in place for years – because of both the red tape involved and sensitivity. To accelerate the process, the European Commission could consider three measures to reduce the reputational constraints the financial sector faces when lending to defence companies.

First, the Commission could temporarily ease the stance on ‘controversial weapons’, by removing exposure to at least some controversial weapons from the considerations that need to be made within the taxonomy framework, and to allow such exposures to be counted towards banks’ green asset ratios.

Though the definition of controversial weapons is not very constraining in practice, because only few EU companies are presently involved in these weapons, the new geopolitical reality may require new financing for producers of, for example, cluster munitions or mines. In many cases, raising funds for companies involved in these weapons will also require amendments to national rules that prohibit their financing.

Second, the Commission should clarify whether nuclear weapons are considered controversial weapons under EU law (which does not appear to be the case), and should clearly articulate its stance on defence investment, as the UK Financial Conduct Authority has done 8 . The Commission could also, based on the EIB precedent, urge EU banks to remove the self-imposed nuclear-weapons financing exclusions they have in place, limited to EU companies and/or non-EU companies selling to EU countries.

Beside banking, many of the ideas being floated to finance EU rearmament rely heavily on private investment. The idea of creating a ‘rearmament bank’ 9 that would finance itself by issuing triple-A bonds, for example, implicitly assumes that there will be the capacity in EU financial markets to invest more in defence-linked funding instruments. Similarly, the European Security and Industrial Innovation Initiative floated on 10 March by Italy’s finance minister assumes that the private sector will be willing to leverage €17 billion of public money into €200 billion of funding for defence companies, through a debt tranching structure 10 .

The number of defence-themed investment funds doubled last year to a record 47 11 – including a European-only defence exchange-traded fund 12 launched on 11 March – following decades during which such products were hardly available. And survey evidence suggests that investors feel defence and nuclear exposure should be allowed in ESG funds, at least in “some circumstances” (Jones and Templeman, 2022). Yet, while inflows to defence-focused funds will certainly increase, these funds are a small subset of the EU market – only 24 defence-labelled funds marketed in the EU, for €7.5 billion in assets, according to Bloomberg data[13].

To push the change and overcome reluctance related to the sensitivity of defence investment, the third step the Commission could take would be to formally encourage EU investment funds– except for Article 9 funds – to invest a set percentage of their assets in EU defence or defence-related companies, thus easing reputational risk concerns for the EU fund industry. At present, total assets under management are approximately €5 trillion in Article 6 funds and €7 trillion in Article 8 funds. If, for example, all Article 8 funds were to invest 5 percent of their assets and all Article 6 funds were to invest 10 percent of their assets in EU defence, this would already match ReArm EU’s €800 billion. If the Commission sees defence investment as problematic for Article 8 funds, then a higher percentage applied to Article 6 funds only could achieve a similar result.

The Commission could also consider temporary removal of defence exclusions from minimum climate benchmark requirements. The link between defence and environmental objectives is not entirely obvious in the first place, and this would allow more investment to flow towards the sector across both passive and active financial products.

If Brussels wants to see a fast re-alignment of private capital towards defence, it should send a clear message to the financial industry that security is now considered a precondition for achievement of all other policy goals – including ESG goals. Many options can be pursued, but it is essential that the Commission aims for clarity and leaves no grey areas on how it expects the financial sector to get involved.

References

Draghi, M. (2024) The future of European competitiveness, Part B | In-depth analysis and recommendations, available at https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en

EAFMA (2024) ‘Trends in the European Investment Funds Industry in the fourth quarter of 2024 & Full results of the Full Year 2024’, Quarterly Statistical Release 100, European Fund and Asset Management Association, available at https://www.efama.org/sites/default/files/files/quarterly-statistical-release-q4-2024.pdf

ESMA (2024) Final Report Guidelines on funds’ names using ESG or sustainability-related terms, European Securities and Markets Authority, available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/document/final-report-guidelines-funds-names-using-esg-or-sustainability-related-terms

European Commission (2023) ‘Commission notice on the interpretation and implementation of certain legal provisions of the EU Taxonomy Regulation and links to the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation’, C/2023/3719, available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2023_211_R_0001

Jones, D. and L. Templeman (2022) ‘Will defence and nuclear pivot to ESG?’ dbSustainability, April, available at https://www.dbresearch.com/PROD/RPS_EN-PROD/PROD0000000000522744/dbSustainability_Spotlight%3A_Will_defence_and_nucle.PDF

MSCI (2024a) MSCI Global ex Controversial Weapons Indexes Methodology, available at https://www.msci.com/indexes/documents/methodology/4_MSCI_Global_ex_Controversial_Weapons_Indexes_Methodology_20240820.pdf

MSCI (2024b) MSCI EU Taxonomy Methodology, MSCI ESG Research, available at https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/30916262/MSCI+EU+Taxonomy+Methodology+June+2024_Public-v2.pdf/f6400e8b-9066-2ecb-5e26-99b629f0c969?t=1719341659133

Willman, T., P. Diaz-Varela Peña, C. Manchón, J.O. Huidobro, J. Tongue and M. Essikouti (2024) ‘ESMA Fund Names Rule: Over Half of EU Funds Must Divest or Rename to Meet Compliance’, Clarity AI, 5 September, available at https://clarity.ai/research-and-insights/regulatory-compliance/esma-fund-names-rule-over-half-of-funds-need-to-divest-or-change-name-in-coming-months/

For more information about Algebris and its products, or to be added to our distribution lists, please contact Investor Relations at algebrisIR@algebris.com. Visit Algebris Insights for past commentaries.

Any opinion expressed is that of Algebris, is not a statement of fact, is subject to change and does not constitute investment advice.

No reliance may be placed for any purpose on the information and opinions contained in this document or their accuracy or completeness. No representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in this document by any of Algebris Investments, its members, employees or affiliates and no liability is accepted by such persons for the accuracy or completeness of any such information or opinions.

© Algebris Investments. Algebris Investments is the trading name for the Algebris Group.