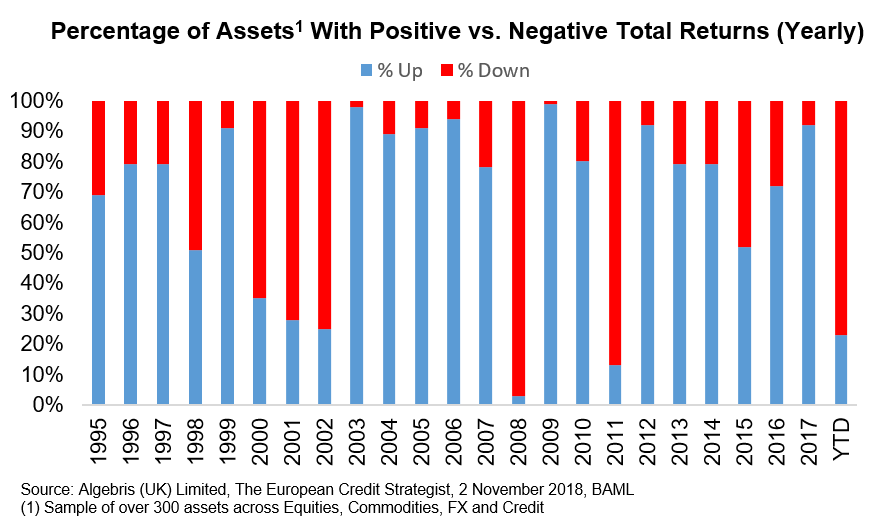

2018 has turned out to be a year of divergence between the US and the Rest of the World, with an unwind of the global synchronised growth and the goldilocks environment we had in 2017. With a slowdown but no recession on the horizon financial markets have underperformed the economy: nearly 80% of assets are down year-to-date.

Will next year see a recovery in risk assets? Will Europe and EM continue to underperform? Or will the US economy catch-down, hurt by trade tensions and a lack of fiscal ammunition?

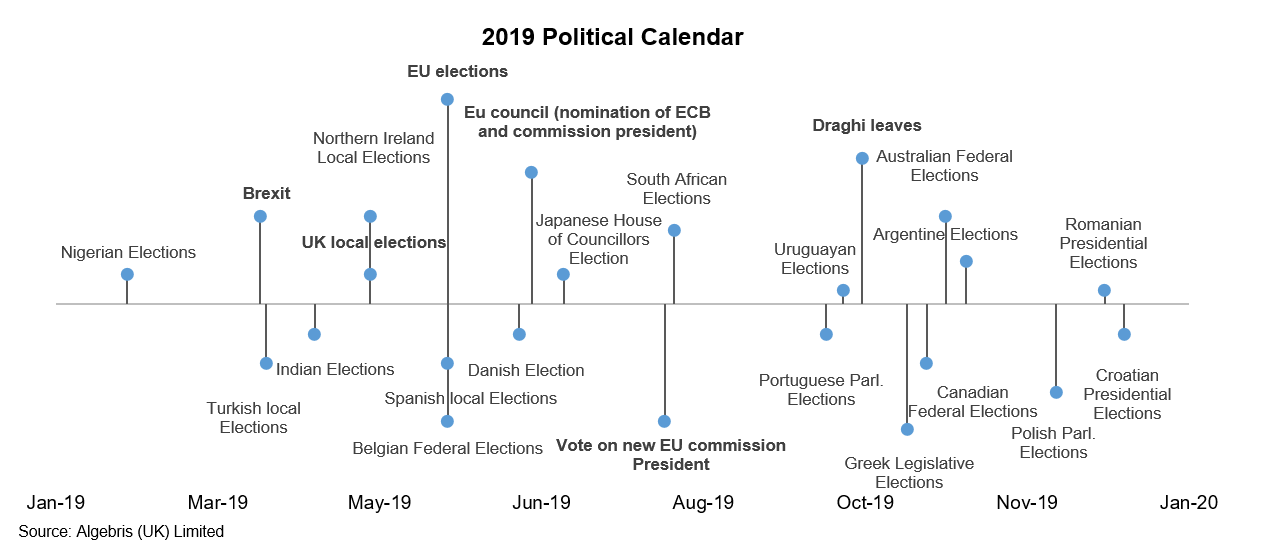

Our base case is a continuation of the current divergence. We believe global growth will remain positive, but still skewed in favour of the US. According to the IMF’s latest Economic Outlook, in 2019 US growth is expected to soften slightly to 2.5%, and has already been revised down by 0.2%. However, tailwinds from the fiscal stimulus will gradually fade, and signs of a pass-through of tax cuts into capex and higher demand remain tentative. China will continue to slow, despite having switched back on its credit stimulus engine. This will likely drag onto other emerging markets and European exporters. Europe will continue to face uncertainty, with European elections coming up in May and continuing negotiations in the UK and Italy around Brexit and the fiscal budget.

The bull case is one of convergence, which could happen with a reversal of US-China trade tensions. Whilst we do see a potential thaw between the two administrations, this is unlikely to be long-lasting, due to the large list of outstanding issues to iron out.

Finally, there is a much-talked bear case of disruption, meaning a global recession or an overheating of the US economy causing the Fed to overreact and tighten financial conditions excessively – potentially together with tail events in the UK and Italy. Contrary to what is becoming consensus, we believe fears of a recession are overdone, and that Brexit as well as the Italian budget negotiation may generate volatility, but will eventually be resolved.

In 2018, we have seen the market pendulum swinging all the way back from euphoria to fear, especially in Europe, where hopes of reform following French elections in 2017 have been bashed by populism. Today, we are cautiously optimistic for 2019, given the sharp re-pricing across risk assets. Ultimately, the reaction function of central banks will determine when and how strongly the pendulum will swing back to positive. The Federal Reserve is well ahead of its peers in the path towards normalisation, but we believe a fading fiscal stimulus and a tightening in financial conditions may prompt a pause in its hiking cycle. As we wrote previously, we believe the ECB has missed the train on rate hikes, boxing itself in with an ill-timed end to quantitative easing, and will try to make up for it with dovish forward guidance. Even though a slowdown is likely and political volatility will likely persist in our base case scenario, a lot of bad news is now priced in by risk assets and European credit in particular – more on this in the next pages. This, in our view, presents an opportunity for patient investors.

Our Key Views for 2019

1. Will we see further escalation in trade tensions next year?

We think trade tensions may remain elevated next year, while a temporary agreement may be reached at the upcoming G20 in order to calm the markets.

Following the APEC summit this month, we believe chances have increased that China and the US may not reach a permanent agreement at the G20. If an agreement is reached, it may be a temporary one – with a list of long-term demands from the US still pending, particularly on intellectual property and defence related issues.

Recently, President Xi has reaffirmed China’s commitment to increase imports and make it easier for foreign companies to invest in China. That said, demands from the United States will likely aim at containing China’s growing technological and military influence in the world. This means that, as highlighted in VP Pence’s speech, a list could include both improvement on terms of trade/investment as well as geo-political demands including a reduced presence in the South China Sea. Agreeing on this all-encompassing list of demands will be more challenging for China, and could result in a persistence of trade tensions next year.

The US may also increase trade restrictions on European exports, especially for automotive products on which it is running a €36bn deficit. This year, while there were some tariffs implemented by both sides, European trade with the US remained relatively unscathed. We believe the US did not escalate trade tensions with Europe, on concerns that it may push Europe closer to China, with resulting negative impact to US financial markets from three separate trade wars running at the same time, including China and NAFTA. In 2019, with NAFTA renegotiated and a truce with China trade tensions, President Trump could refocus his attention on reducing the European trade deficit.

2. Who has more to lose from a trade war?

The US and China, more than the Rest of the World, according to the IMF’s October World Economic Outlook. The IMF estimates that a trade war could reduce GDP by over -1.5% in China and over -1% in the US, with the largest impact in 2019/2020. The IMF estimates that Europe may be relatively insulated, with only a -0.4% GDP growth impact. However, the loss for Europe could be more severe if the Trump administration targets Europe more directly next year on auto parts exports.

3. Brexit: what kind of deal should we expect?

We believe a kick-the-can extension deal is the most likely outcome. Despite important steps towards an agreement have taken place namely, the backing from May’s Cabinet for the proposed Draft Withdrawal Agreement and Political Declaration and the EU summit on November 25th signing off on the agreement – the road to a final deal is still far away.

A key obstacle will be trying to obtain Parliamentary approval for the draft deal, with a vote most likely held in early December. In order to pass her Brexit deal through Parliament, PM May needs at least 320 votes. This will require defections from Labour in order to offset the loss of support from the DUP along with that of certain Conservative party members.

Today, we believe it is more likely that Parliament will vote against the deal given that members from both wings (remain and leave) would benefit from this draft failing, albeit for very different reasons. A “no” vote from Parliament doesn’t mean Brexit negotiations end. Instead, such a vote would send the UK and the EU back to the negotiating table, thereby extending the negotiating period in order to find a way for May to cobble together a majority in Parliament.

Ultimately, we expect a “damage control” deal similar to the draft passed through Cabinet on November 14.

4. Fragile politics in Italy: will the coalition between the Five Star Movement (5S) and the Northern League (NL) continue in 2019?

We believe there is a chance of Italy’s running coalition breaking up next year, possibly after the European elections next May. Since the Italian General Election held last March, the NL led by Salvini has been steadily gaining consensus, reaching around 30-35% in recent polls. This rise to power was driven by winning greater cooperation from other EU countries in dealing with migration, as well as from an easing of unfavourable comments towards Southern Italy.

If the coalition between 5S and the NL were to fail, it is possible that the next government may be a centre-right coalition led by the NL allied together with Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (FI). Potentially, a NL alliance with Forza Italia could account for about 41% of votes today, up from 31% at the time of the general election. Such centre-right alliance would most likely have a business-focused agenda.

Failure to deliver on its promise of universal basic income, which should come into effect in mid-march 2019, could further penalise the Five Star Movement and could accelerate the break-up of the 5S-NL coalition.

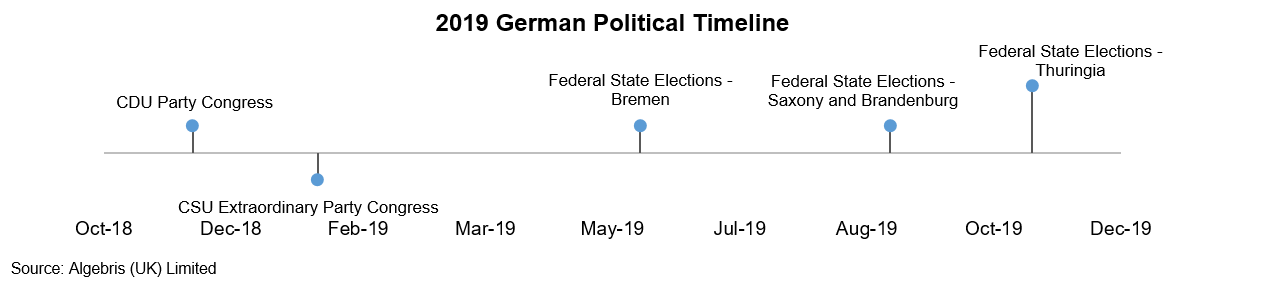

5. Fragile politics in Germany: who will succeed Merkel as CDU party head?

The CDU party congress will take place on December 7th. Without underestimating the support by Merkel and her followers for Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (AKK), we believe Friedrich Merz will take over CDU’s leadership but will subsequently have to soften his tone, in order to cooperate with Merkel and the existing coalition.

Value-conservative and economy-liberal Merz represents the well-received opposite of Merkel, and is a familiar yet refreshing figure for the CDU, having disappeared from politics since 2009. As chairman of the Atlantik-Brücke, Merz could improve relations with the US, while being supportive of EU reforms. Called the “Macron of Germany“, Merz once criticized Merkel’s lack of reaction to Macron’s proposals and recently called for Germany to take the “driver’s seat to bring the EU forward in terms of growth and prosperity”.

Merz’s opponent Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer symbolizes a continuation of present policy, although trying to reject the image of a “Mini-Merkel” through a more conservative stance on marriage and deportation. We believe that little would change under her reign and hence no real benefit to the political landscape of Germany would arise.

Right-wing outsider Spahn seems out-of-favour having made unpopular comments in the past and appearing too junior for the role. We believe he’ll withdraw his candidacy shortly before the party congress, giving the lead to Merz by handing over his votes. Advertising a clearer stance on e.g. migration, Merz could then gain back previously-fled protest voters from AfD by sharpening the profile of CDU. This could present at the next federal state elections of Saxony, Brandenburg and Thuringia in fall 2019, states in which AfD has potential to become or already is strongest party in polls.

In the tail risk scenario of new elections, we see a “Jamaica” (CDU, FDP, Greens) or even CDU/Greens-only coalition as a plausible outcome, following the strong gains by the Greens in Bavaria and Hesse, recent statements of willingness by FDP party leader Lindner and Merz praise of the Greens program for the European elections in 2019. In our view, such coalitions would be overall favourable for Europe and a positive development against populism.

6. How will EU elections affect Europe?

The next elections to select the EU Parliament, which appoints the European Commission, will take place in May 2019. These elections will confirm, or limit, the rising power of European populists.

Polls are indicating a fragmented parliament, with the two largest coalitions – the European People’s Party and the Social Democrats – losing some ground to anti-EU parties. Since the inception of EU elections, participation has steadily fallen, which has tended to benefit more motivated and radical minorities. We expect this election cycle to be no different. On the bright side, euro-sceptics remain split into three different coalitions; the ECR, the ENF and the EFFD. Seeing one united anti-EU party is unlikely given conflicting aims, views and personalities of the populist movements, but it’s a risk to closely monitor going into the elections.

The downside risk from these elections will likely be to further fragment the European Parliament, slowing down the development of the EU’s institutional framework. The election outcome will have profound implications for urgent pending projects such as the completion of the European Monetary Union, but also the EU’s crisis response capabilities and reaction speed. We believe one likely silver lining of the election however, to be that a further rise in populist parties will finally trigger a reaction from establishment parties in the various member states – Germany and France in particular – towards a broader EU consensus on burden sharing in immigration policies, at the very least. We have already seen some movement in this direction in the recent discussions between Ms Merkel and Mr Macron about an EU budget.

7. How will central bankers react in 2019?

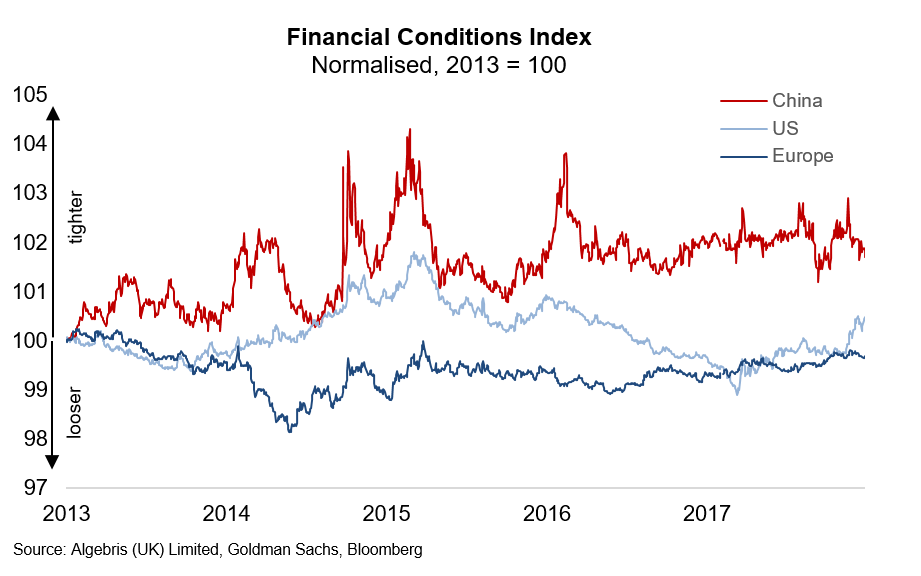

The Federal Reserve is well ahead of its global peers in normalising monetary policy, thanks also to the recent fiscal stimulus and previously, a quicker restructuring of private balance sheets. Historically, the Fed has paused hikes or adopted a more accommodative monetary stance during a hiking cycle only if worried about a tightening in financial conditions – i.e. if credit spreads widen substantially or growth forecasts drop below potential (see also GS Research). Neither condition has yet been fully satisfied yet. However the recent widening in credit spreads has tightened financial conditions for firms. Together with fading fiscal stimulus and a continuation in trade wars, this could prompt more weakness in labour markets as shown by recent jobs data – and in turn, a pause in the hiking cycle.

In the Eurozone, we believe the ECB will normalise rates from negative to zero towards the end of 2019 and into 2020, as we have stated before. Wage growth remains strong in core countries, however, unemployment remains high elsewhere in Europe, and the pass-through from wage growth to broader inflation measures appears limited and below the ECBs forecasts, especially given the recent drop in oil prices. In addition, the recent tail risks in Italy and the UK may have further constrained the flow of credit.

Against this environment of slowing growth and rising global risks, the central bank’s planned end to quantitative easing purchases appears ill-timed. To compensate for a potential policy error, we believe the ECB will change its language in December to acknowledge that risks are now tilted to the downside, and will soon announce a new TLTRO for banks. Should risks escalate further, then the ECB may react with more dovish forward guidance on rates. We expect the QE reinvestments to continue using the current ECB capital key, with perhaps a small increase to the average maturities of bonds purchased.

In the UK, we think the Bank of England will have a hard time to meet markets’ expectations on rate hikes, currently at one hike per year, over the next three. On the one hand, in the event of a Brexit deal next year, a rise in Sterling would constrain a pick-up in inflation, together with persistent growth risks.

On the other hand, a hard Brexit would leave the BoE against the wall given elevated leverage in private sector balance sheets (debt to income is projected at 146% in 2023 by the OBR) and falling house prices: hiking rates to defend its currency, as the Governor hinted, would be unrealistic. We estimate a potential loss of 7.5% of GDP from Brexit, see The Silver Bullet | The High Cost of a Hard Brexit.

Conclusions: Opportunities for Patient Investors

2018 was as negative for asset returns as 2002, 2008 or 2011; all years when global economies experienced either a crisis or a sharp economic slowdown.

This year’s dismal performance in financial markets, instead, has been accompanied by still-positive growth across economies. Even though many economists are tempted to predict an end to the cycle, macro data does not suggest a recession or overheating.If the economy is still going along then, markets underperformance must have been due to other causes: on the one hand, the realisation that central bankers are no longer holding the hand of investors and on the other, that irresponsible politicians may end up funding their unrealisable promises to their electorates with investor money. Put differently, monetary policy has little ammunition left to help, and central bankers are increasingly worried about replenishing their dry powder, rather than the economy and fiscal policy is often in the hands of short-term thinkers.

Meanwhile, the return of volatility and the liquidity unwind in markets have already created some real damage to both governments and companies. Weak sovereigns have had an increasingly difficult time refinancing: Argentina, Turkey, Barbados, Costa Rica, Sri Lanka as well as Italy saw their spreads widen. General Electric, Nyrstar, Boparan, Pizza Express, Astaldi, Aldesa, CMC among corporates suffered widening and downgrades.

Today, however, valuations suggest the pendulum of sentiment has swung from euphoria into fear. A recession-like amount of losses is implied by current asset prices, and particularly in European credit markets – trading just shy of February 2016 spread levels. Investors are holding credit in the UK or Spain are rewarded more than in most emerging markets, adjusting by ratings. Equally, the extra premium for holding high yield bonds in Europe vs US is at a post-crisis high since 2011. Despite that, corporate fundamentals remain mostly unchanged, with European firms still deleveraging: JP Morgan research estimated net debt / EBITDA at around 4.2x in October for European high yield firms, up from 3.7x at its lows but still shy of around 5.3x in 2009. This contrasts with the accumulation of leverage present in US high yield and leveraged loan markets. In other words, while leverage is high across US and EM credit markets, and spreads still around or below long-term averages, corporate leverage and bank capital remain stable in Europe, with valuations pricing elevated tail risk.

Even though political-driven volatility is likely to continue, we believe this disconnect between recession-like valuations vs still positive fundamentals presents an opportunity for patient investors.

Going forward, the question remains whether politicians in the US, UK and Italy will eventually soften their stance on trade, Brexit and deficit negotiations, or if they will maintain an antagonistic stance regardless of the economic damage.

If you don’t know where you are going, you will probably not get there, says the Cheshire Cat to Alice. Policymakers in the UK and Italy who have made unrealistic promises to their electorates will eventually have to back down – with a compromise deal on Brexit and a lower budget deficit in Italy (see also: The Silver Bullet | The Economics of Populism). The road to a compromise is indeed difficult for markets to digest. But it may not be enough to create a recessionary shock for the economy, as many investors fear.

Per ulteriori informazioni su Algebris e i suoi prodotti o per farsi inserire nella lista di distribuzuione, si prega di contattare il dipartimento Investor Relations all’indirizzo algebrisIR@algebris.com. Gli articoli passati sono disponibilii sul sito Algebris Insights

Questo documento è emesso da Algebris (UK) Limited. Le informazioni contenute nel presente documento non possono essere riprodotte, distribuite o pubblicate da alcun destinatario per qualsiasi scopo senza il preventivo consenso scritto di Algebris (UK) Limited.

Algebris (UK) Limited è autorizzata e regolamentata nel Regno Unito dalla Financial Conduct Authority. Le informazioni e le opinioni contenute nel presente documento hanno solo scopo informativo, non hanno la pretesa di essere complete o complete e non costituiscono una consulenza in materia di investimenti. In nessun caso qualsiasi parte del presente documento deve essere interpretata come un’offerta o una sollecitazione di qualsiasi offerta di qualsiasi fondo gestito da Algebris (UK) Limited. Qualsiasi investimento nei prodotti cui si fa riferimento nel presente documento deve essere effettuato esclusivamente sulla base del relativo Prospetto informativo. Queste informazioni non costituiscono una Ricerca di Investimento, né una Raccomandazione di Ricerca. Con il presente documento Algebris (UK) Limited non organizza o accetta di organizzare alcuna transazione in qualsiasi tipo di investimento, né intraprende alcuna attività che richieda l’autorizzazione ai sensi del Financial Services and Markets Act 2000.

Non si può fare affidamento, per nessun motivo, sulle informazioni e sulle opinioni contenute nel presente documento, né sulla loro accuratezza o completezza. Nessuna dichiarazione, garanzia o impegno, esplicito o implicito, viene data in merito all’accuratezza o alla completezza delle informazioni o delle opinioni contenute in questo documento da parte di Algebris (UK) Limited , dei suoi direttori, dipendenti o affiliati e nessuna responsabilità viene accettata da tali persone per l’accuratezza o la completezza di tali informazioni o opinioni.

La distribuzione di questo documento può essere limitata in alcune giurisdizioni. Le informazioni di cui sopra sono solo a titolo di guida generale ed è responsabilità di ogni persona o persone in possesso di questo documento informarsi e osservare tutte le leggi e i regolamenti applicabili di qualsiasi giurisdizione pertinente. Il presente documento è destinato esclusivamente alla circolazione privata per gli investitori professionali.

© Algebris (UK) Limited. Tutti i diritti riservati. 4° Piano, 1 St James’s Market, SW1Y 4AH.