What should investors do in a market where there’s nothing left to buy?

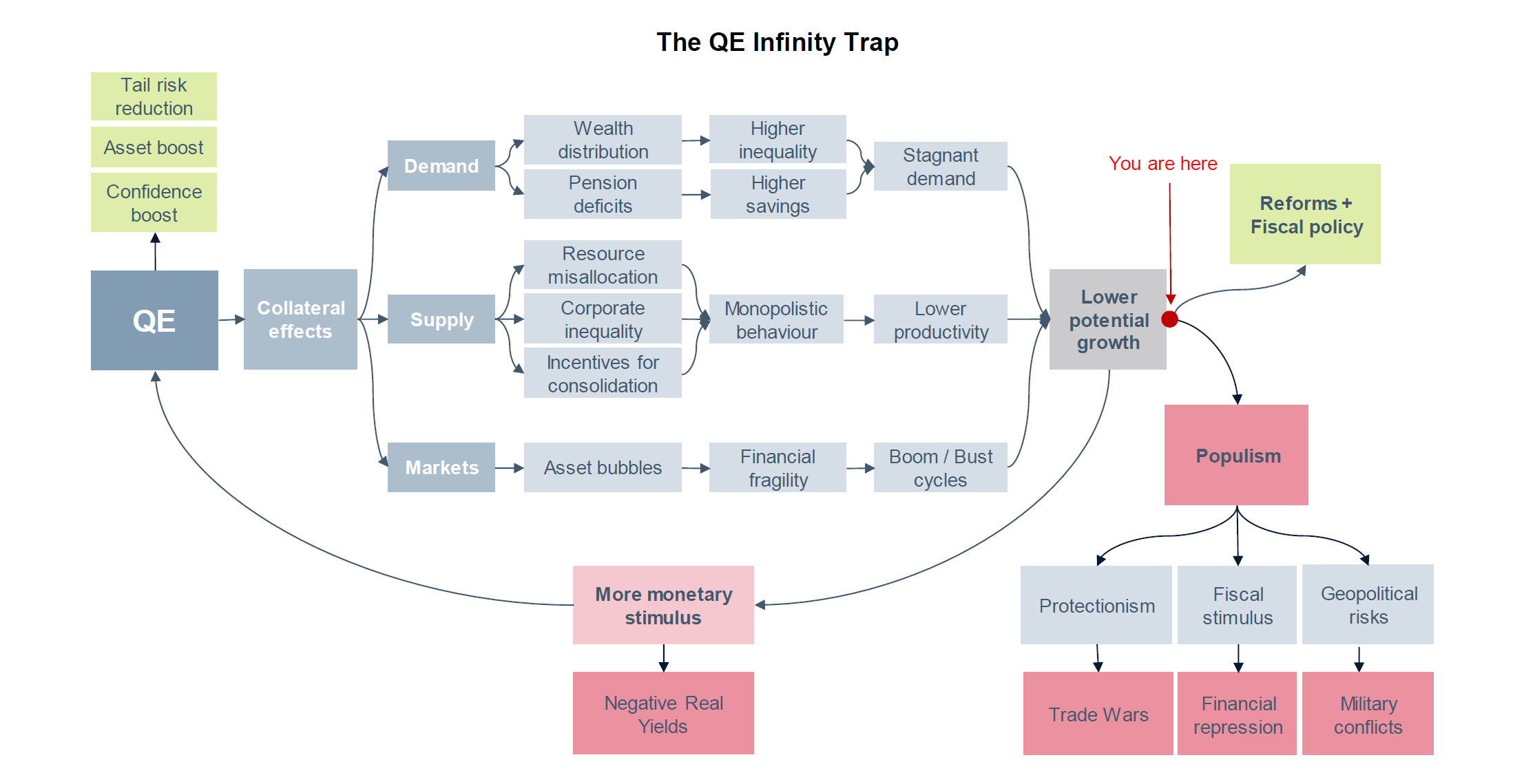

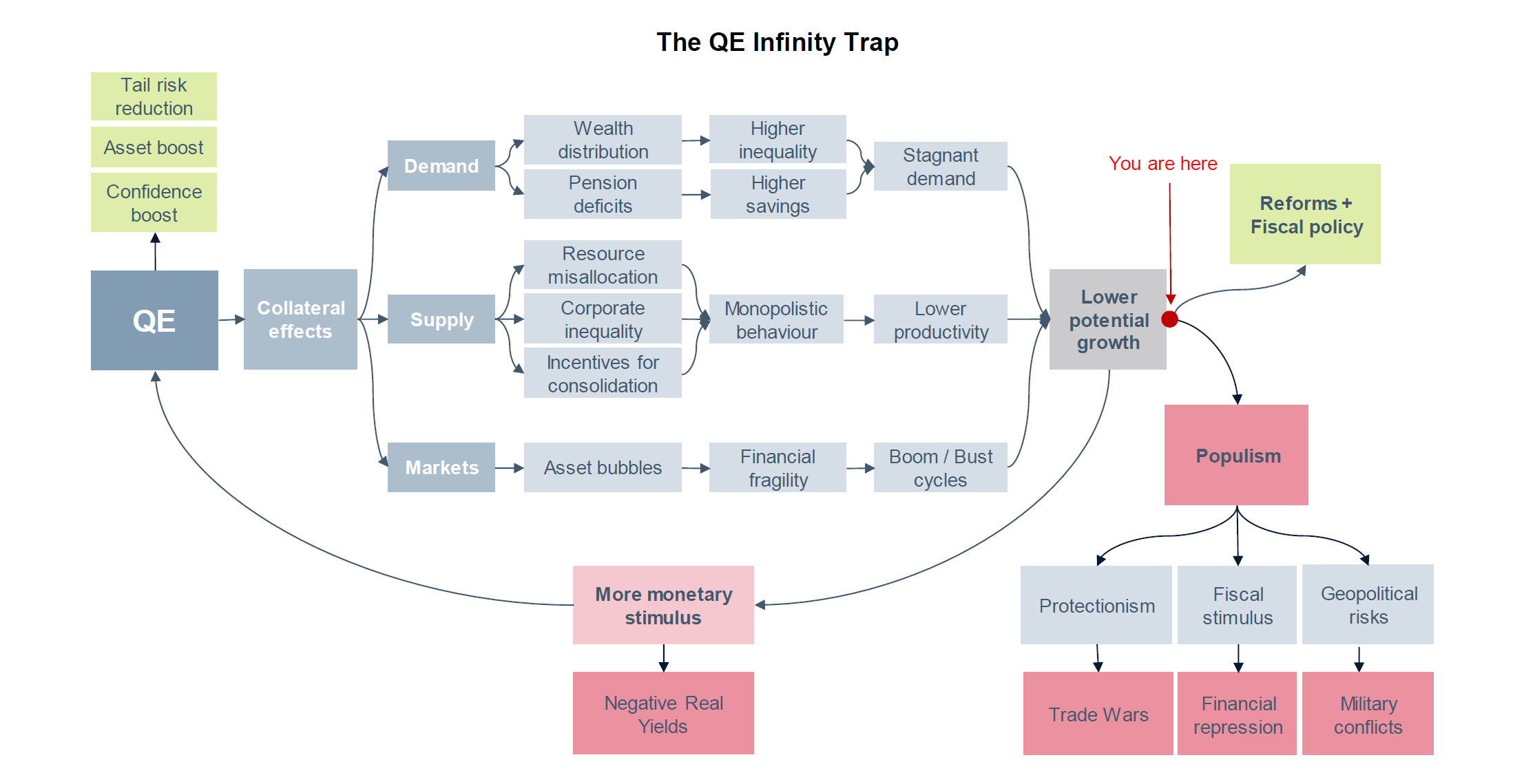

One of the premises for central bank action in the last decade was that lowering the cost of money and the return on risk-free assets would push investors to dump these and buy higher return riskier assets instead. In turn, this would funnel fresh capital to firms, boosting business investment and growth.

After a decade of quantitative easing and declining nominal and real interest rates, this substitution effect isn’t working as planned: assets with a direct link to interest rates continue to outperform vs assets whose performance depends on economic growth.

Investment grade bonds and double-B high yield paper are at record tight spreads vs lower rated high yield firms, gold is at a record high vs copper, large firms and tech/growth stocks continue to outperform vs small caps and value equities.

Long central banks, short growth

This is what investors are doing: hiding in assets which benefit from central bank liquidity while shunning what depends on growth. Even though liquidity-proxy assets are already expensive, money keeps pouring in. The largest capital flows in 2020 have been in bonds – $88bn, off the charts for a first quarter – leaving distressed credit, European and emerging market stocks and US small caps relatively unloved.

The irony is investors are doing exactly the opposite of what central banks expected to achieve in the first place.

Are investors rational in their behaviour? Some rightly point out that price discrimination is a sign of market efficiency. For example, retailers or energy firms in the high yield market trade at distressed valuations because of their obsolete business models, showing investors are buying almost anything, but not everything.

That said, if we exclude a few troubled sectors, risk premia appear very compressed, in a double-hump, polarised distribution: most firms trade at record tight spreads vs a small tail of distressed assets containing only firms and governments at near-term default risk, like Argentina, Lebanon and Zambia.

What does investor behaviour tell us about the economy?

The short answer is – investors’ skepticism may be justified. Central bank liquidity has failed to substantially boost aggregate demand and inflation, particularly in economies where private balance sheets weren’t restructured, like Europe. In addition, ageing population and adaptive expectations have pushed households to save more, rather than spend – Germany is a case in point.

Even though traditional economic thinking postulates that low rates boost demand, empirical evidence is starting to challenge the theory, and some central banks have started to listen – the Riksbank, for example, moved rates back to zero last year.

While the impact of central bank liquidity on demand is weakening, few economists have explored the effects of persistent low rates on supply. In part, this is because supply-side effects may take longer to measure, with causation links which are more difficult to detect.

One phenomenon to which loose liquidity contributes is key though, in our view, and it is observable across industrial sectors: the winner-takes-all effect. Large firms in a leadership position are able to tap cheap capital and can easily implement consolidation strategies and buy out their competitors. In turn, lower competition reduces economic dynamism and productivity.

The game changers

One central banker recently asked us – how should investors behave in a market where there’s nothing left to buy? The answer is investors may be doing the right thing. They know central bank policy is insufficient to boost aggregate demand and inflation, and that it also creates supply-side distortions, if persistent. In turn, investor demand for interest rate sensitive and safe-haven asset in every asset class rewards monopolies and less productive investment, defeating low interest rate policy.

That said, central bank policy has been the only game in town for over a decade. Will policymakers change tack? The game could change in two ways: central banks may turn less accommodative or fiscal policy could lead to a rebound in growth, taking some weight of monetary policy.

While it is highly unlikely that all major central banks would turn less accommodative in the near term, many are starting to note the negative side effects of persistent low rates. In our view, this means the long duration trade of the past decade is largely done.

The alternative is a rebound in growth led by a fiscal expansion – for example in China or Germany. This would cause investor to finally consider allocating capital to growth-sensitive assets. This scenario seems unlikely, with German politics entering an internal reshuffle following recent regional elections, and China having relatively little room for stimulus. In addition, geopolitical tensions are unlikely to fade into US elections, in our view, with the Trump administration still needing to polarise its electorate against external threats to boost support.

The base case is therefore a continuation of the current dovish environment, which we believe will persist despite rising inflation: one step in this direction are the upcoming reviews by the Fed and the ECB, where the two central banks are likely to move to a symmetric inflation range. The result will be flatter or more negative real rates, and lower real returns for long-only bond investors.

Coronavirus strengthens case for L-shaped recovery with QE forever policy

In addition to the above, the recent outbreak from the coronavirus in China is likely to cap an acceleration in the cycle. As we discussed last year in our latest Silver Bullet, our indicators have been showing mixed signals for economic growth, with consumer demand leading thanks to low interest rates, but business investment and credit to the real economy lagging.

The policy impact from the virus is likely to be an expansionary tweak to the fine line between reining in excess financial leverage and boosting growth. However, this means more likely dovish monetary policy rather than a fiscal expansion. The PBoC recently injected over 1tn RMB of liquidity repo markets, cut repo rates by 10bp and cut reduced its reserve ratio by 0.5%, while regulators allowed domestic institutional investors to boost their share of equity holdings. We expect further announcements of fiscal measures to offset the economic impact. Other central banks around the world are likely to delay any tightening too, wary of any short-term impact. In his testimony before Congress, J. Powell warned about the virus impact too, which in our view may lead to an extension of the Fed’s purchases of short term treasury debt beyond April.

Will the coronavirus cause a broad downturn? While the number of daily infections remains high in the epicentre of Wuhan, in recent days these have been declining in the rest of Hubei province and China. Major factories have started to reopen this week, and the amount of news flow around the virus appears to have plateaued as well. Assuming current trends persist, this implies the worst of the outbreak may be behind us, and we would expect the resumption of production to continue through the remainder of February and early March.

What should investors do in a NLTB market?

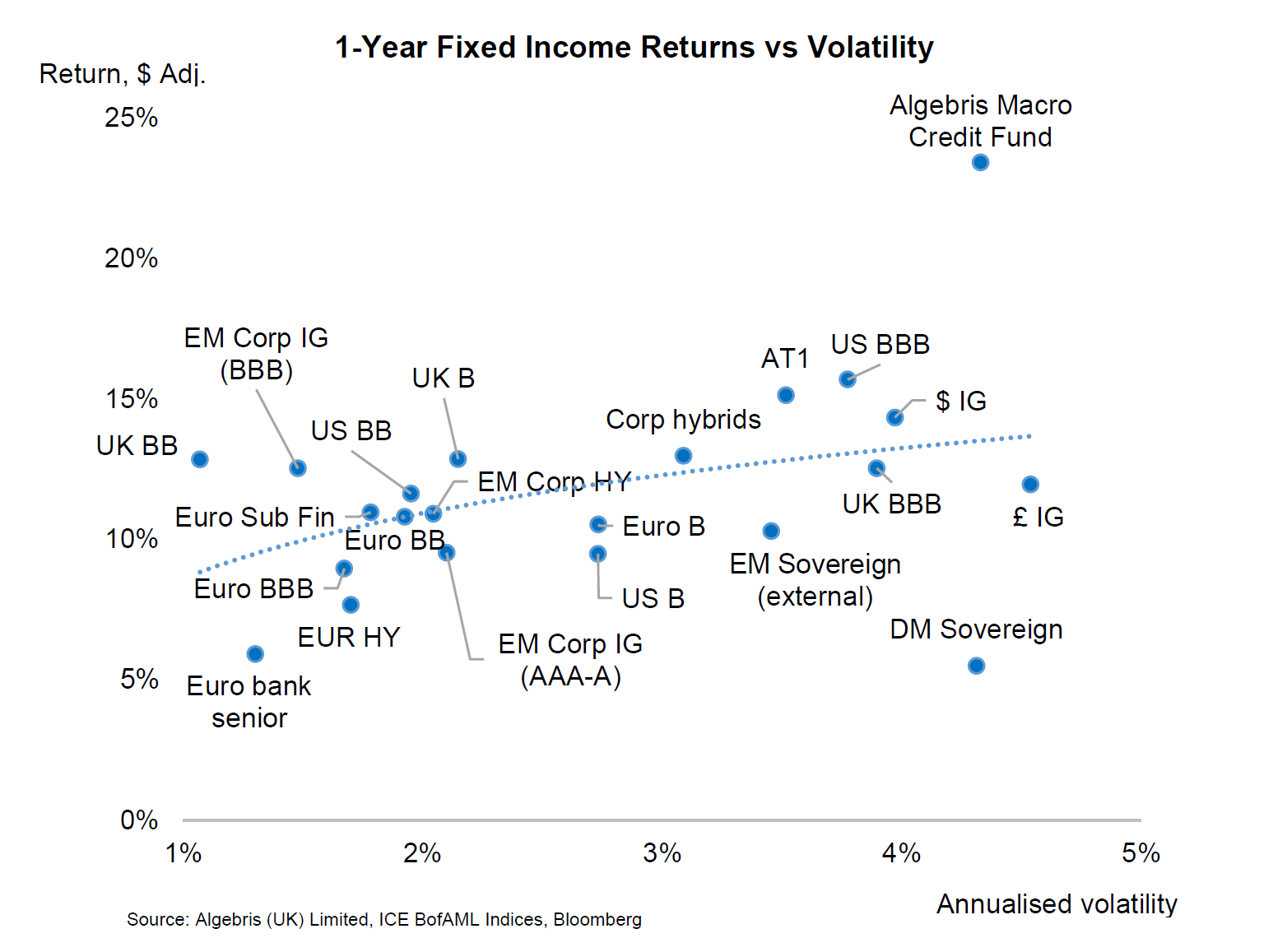

In a recent CNBC interview, Prof. J. Siegel of Wharton said the traditional “60-40 portfolio doesn’t cut it anymore”. These were exactly our thoughts five years ago, when we started thinking about a flexible fixed income opportunities strategy.

Over the past few months as credit spreads reached new tights, we have taken profits on assets with little upside left and asymmetric payoff – like beta credit – and focused on selective long and short situations across sovereigns, corporates and banks.

1. Focus longs on alpha opportunities

We have reduced beta to a minimum. Our bond portfolio is almost fully hedged, with 1-1.5y of credit duration and a monthly VaR of 1.7%, roughly half the risk we had a year ago. We are focusing on concentrated long (or short) positions in issuers with positive (or negative) catalyst. These are the main drivers of our year to date performance, above 3%.

2. Tail hedging and shorts

We believe broad credit spreads, and in particular US high yield double-Bs, represent one of the best macro shorts today for a downside growth scenario, at only 100bp in spread. In emerging markets, we think Turkey and Brazil are vulnerable to too-dovish central bank policies, which have compressed real interest rates to a very thin margin. In Turkey, government policies which support credit easing in the private sector may boost demand in the short-term, but create large balance sheet losses in the medium term.

3. Keep powder dry

Our portfolio construction is currently a barbell between assets with upside, like bonds trading below par with selective upside catalysts, and very liquid assets. This allows us to benefit from market volatility, compared to a fully invested portfolio at an average market yield.

Conclusions: Rebalancing the odds

“The most dangerous thing is to buy something at the peak of its popularity. At that point, all favourable facts and opinions are already factored into its price and no new buyers are left to emerge.”

– Howard Marks

We are positioned for an L-shaped recovery with near-2% growth in the U.S. and near-1% growth in the Eurozone, accompanied by persistently dovish central bank policy. That said, valuations are expensive. Interest rate sensitive assets are very popular. They are at the peak of their performance: investors have been betting on central bank liquidity to continue flowing, without inflation or a pick-up in growth. This is the QE infinity environment we anticipated.

Asset overvaluation does not mean that prices are likely to fall any time soon. But history suggests that starting from real yields this low, even a small move against investors can wipe out a year of returns. Historically, starting from the bottom quartile in real yields meant investors in triple-B bonds lost money against inflation 53% of the times over the following year, using data since 1919. Bonds and bond proxies can continue to outperform in the near term. But investors in these assets are increasingly walking a narrow path between a rebound in growth and a sharper slowdown. Take double-B bonds: if growth rebounds, duration will hurt, without room for spreads to tighten and compensate. In a slowdown instead, some double-B firms will likely drop in credit quality, with their above-par bonds widening in the hundreds of basis points.

Convexity is clearly against who buys the broader market. Central banks have skewed the odds against investors. Our job is to even them out and rebalance them in their favor.

For more information about Algebris and its products, or to be added to our distribution lists, please contact Investor Relations at algebrisIR@algebris.com. Visit Algebris Insights for past commentaries.

This document is issued by Algebris Investments. It is for private circulation only. The information contained in this document is strictly confidential and is only for the use of the person to whom it is sent. The information contained herein may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any recipient for any purpose without the prior written consent of Algebris Investments.

The information and opinions contained in this document are for background purposes only, do not purport to be full or complete and do not constitute investment advice. Algebris Investments is not hereby arranging or agreeing to arrange any transaction in any investment whatsoever or otherwise undertaking any activity requiring authorisation under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. This document does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of an offer to subscribe or purchase, any investment nor shall it or the fact of its distribution form the basis of, or be relied on in connection with, any contract therefore.

No reliance may be placed for any purpose on the information and opinions contained in this document or their accuracy or completeness. No representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in this document by any of Algebris Investments, its members, employees or affiliates and no liability is accepted by such persons for the accuracy or completeness of any such information or opinions.

This document is being communicated by Algebris Investments only to persons to whom it may lawfully be issued under The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 including persons who are authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 of the United Kingdom (the “Act”), certain persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, high net worth companies, high net worth unincorporated associations and partnerships, trustees of high value trusts and persons who qualify as certified sophisticated investors. This document is exempt from the prohibition in Section 21 of the Act on the communication by persons not authorised under the Act of invitations or inducements to engage in investment activity on the ground that it is being issued only to such types of person. This is a marketing document.

The distribution of this document may be restricted in certain jurisdictions. The above information is for general guidance only, and it is the responsibility of any person or persons in possession of this document to inform themselves of, and to observe, all applicable laws and regulations of any relevant jurisdiction. This document is suitable for professional investors only. Algebris Group comprises Algebris (UK) Limited, Algebris Investments (Ireland) Limited, Algebris Investments (US) Inc. Algebris Investments (Asia) Limited, Algebris Investments K.K. and other non-regulated companies such as special purposes vehicles, general partner entities and holding companies.

© 2020 Algebris Investments. Algebris Investments is the trading name for the Algebris Group.