The last decade will be remembered as a boon to investors. In an attempt to fight the financial crisis, central banks boosted asset prices to record highs. They won a battle, but didn’t win the war. Quantitative easing saved the economy from potential depression, but introduced a number of side effects, in a decade of persistent low interest rates and asset inflation, but stagnant productivity.

This era of monetary dominance may be about to end. In the next decade, we believe governments will push to find new solutions, alternatives to the kick-the-can economics that perpetuated across debt-based democracies since the 1960s.

On the one hand, this is because central banks’ powers are limited – more asset purchases and lower interest rates may actually be self-defeating, as we have seen in the Eurozone. On the other hand, rising wealth inequality, low productivity and increased financial fragility call for immediate intervention. Put differently, the current policy mix where one-size-fits-all monetary tools have acted as a painkiller against structural issues is no longer sustainable.

In this final investor letter for 2019 and for the decade, we make a few predictions for investors:

1. Governments will increasingly use fiscal deficits to spend their way out of trouble and in an attempt to escape Japanification. Japan’s recent $120bn stimulus, the largest since Abenomics, is a case in point – but the narrative is changing globally towards fiscal profligacy.

2. Central bankers will sign a Faustian Bargain, getting stronger powers but gradually giving up independence. This means they may keep rates low in the face of rising inflation, for example implementing yield curve control or maybe even funding direct investment.

3. There may be a more radical version of monetary-fiscal policy, to emerge at the next slowdown. At the extreme, this may follow the contours of modern monetary theory in the US, or QE for the people in the UK. Both models are currently championed by the opposition.

4. The result could be a redistribution of wealth from Wall Street to Main Street, with negative real returns for investors and higher wages for voters. This may be accompanied by a much-needed reform of tax systems and anti-trust regulation.

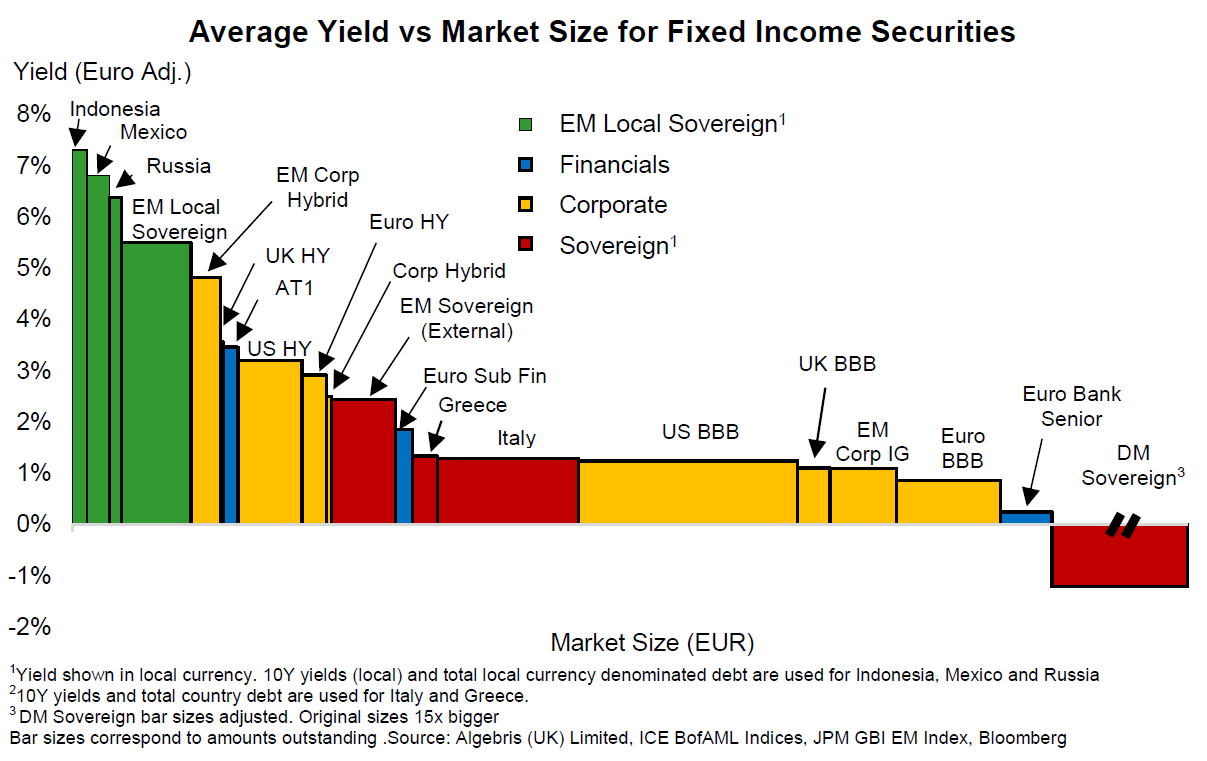

5. Fixed income investors will have no choice but to accept passive, negative real returns in government paper, or invest in riskier debt for positive returns.

So, while the consensus outlook for 2020 is that of a benign slow recovery in markets, on the recent signing of a trade truce between the US and China as well as increased clarity on the UK-European relationship, we see more risks on the horizon. These risks are significant for investors, but may be necessary to fix a growth model which is increasingly imbalanced.

Rising inequality, stagnant productivity and the failure of monetary anaesthetics mean policymakers will stop kicking the can and finally dare to fix the accumulated problems – or break the system.

For these reasons, we enter 2020 aware of the upcoming risks and volatility, but also confident that a truly active approach is the right one to navigate these markets.

Our Key Views for 2020

What will change at the Fed and ECB monetary policy strategy reviews?

Central bankers deserve credit for saving our economy from the 2008 financial shock. However, the scorecard of quantitative easing and the so-called monetary policy 2.0 remains mixed. On the one hand, zero or negative interest rates and asset purchases have reinstated confidence and prevented a deeper slump. On the other hand, this persistent monetary anaesthetic has come with several side effects, including an increase in social and corporate inequality, asset bubbles and fragility in the financial system as well as anaemic growth and inflation.

Today, central banks are increasingly under pressure to fix these economic ills, as well as to step up to new challenges. Their powers, however, are increasingly limited. In 2007, the Fed had 500bp of room to cut rates, as it did in the early 2000s. Starting from a Fed Fund target range of 1.50-1.75%, it now has limited space for manoeuvre.

Like super heroes challenged by a new threat, central banks are searching for new powers.

In November 2018, the Federal Reserve announced a review of its strategy, tools and communication practices, with results to be announced in the first half of 2020. The ECB too announced a review of its strategy, to take place in the first half of 2020.

How will central banks change their mandate and tools to face up to new challenges?

The quickest solution against slowing growth has been for central banks to implement more of the same. The ECB cut its deposit rate from -0.4% to -0.5% in September, restarting asset purchases “for as long as necessary”, at a pace of 20bn a month. The Fed also restarted growing its balance sheet by buying short term debt, even though it refrains from classifying it as QE.

Inflation expectations remain muted though, particularly in the Eurozone. One reason is that negative rates have depressed bank profitability and constrained bank lending activity – the mechanism at the core of monetary policy transmission from banks to the real economy. Skepticism on the effectiveness of persistent negative rates is rising from various members of the ECB’s governing council as well as other central banks, like Sweden’s Riksbank, which recently hiked its repo rate back to zero.

If central bankers’ tools are increasingly constrained and less effective, their ability to work in tandem with other policymakers will be the key factor to determine success for future policies. Christine Lagarde, the ECBs new President, plans to align Eurozone monetary and fiscal policies. This may be easier said than done. France is leading Europe’s PMI rebound thanks to its stimulus plan. However, German leadership appears still focused on internal debates: a recent win by the SPD’s left-wing candidates threatens to jeopardise the already fragile CDU-SPD coalition.

Absent coordination with fiscal policy, the alternative option is for central banks to go at it alone. This means a more aggressive, proactive response, including the implementation of modern monetary theory or QE for the people: asset purchase programmes directly linked to the real economy.

Will it work?

Current QE programmes targeted the real economy only through the lens of financial markets, via the wealth effect and lower refinancing costs from asset purchases. However, this also benefited large bond borrowers and asset owners more than small businesses and the have-nots, in turn favouring industrial consolidation, a concentration of wealth and over time, lower competition and productivity. Targeting the real economy directly from the bottom-up, in our view, is likely to be more successful in generating inflation and growth.

However, taking monetary policy into the realm of fiscal and industrial policy will open the door for politicians to enter the situation room and exert a stronger influence on central banks themselves.

It will be a Faustian bargain: central bankers will gain new tools, but lose their independence.

For investors, navigating the era of monetary policy 3.0 will be a much tougher challenge than its current version. Central banks will be able to boost the economy more directly, yet their boost will also cause even more distortions. Governments may free-ride low interest rates to issue more debt, increasing their credit risk over time. Inflation may finally rise, while asset purchases will likely keep a lid on bond yields, delivering negative real returns. The last monetary party was a boon for investors, but theres hardly a free lunch in economics. This time around, the tab will be on Wall Street.

Will we see fiscal spending globally in 2020?

Its too early to call for a large scale fiscal stimulus in 2020 – even though some countries are starting to think about it. We think substantial new stimulus is unlikely in the US, Germany and China in the near term.

That said, the global narrative is changing, and some governments are tilting their stance towards fiscal easing. One illustration of the hand-off from monetary to fiscal policy is taking place in Japan. The government has announced a$120bn stimulus package for 2020, which could boost the economy by 1.4%, according to government estimates. This is similar in size to the 2016 stimulus, which generated a growth surplus of 1.3%. As details of the package are yet to be released, we question if this this comparison is fair and whether there will be a positive spill-over effect to neighbouring economies.

While its impact on growth remains uncertain, what is clear is that this fiscal stimulus will ease pressure on the BoJ to cut its policy rate further into negative territory. The BoJ has been among the most hawkish central banks relative to market expectations this year, keeping its policy rate on hold. This year Japans Financial Services Agency estimated that 50% of Japans regional banks are currently unprofitable: to prevent financial system risks, Japan has effectively been forced to shift the burden of economic stimulus from monetary to fiscal policy.

In Europe, talks of a renewed stimulus in Germany may prove wishful thinking, as the CDU-SPD coalition is still struggling for leadership. That said, France has been gaining momentum over Germany since President Macrons election, registering a lead in recent PMI data as well as in new company registrations and foreign investment. In the UK, the new Johnson government may also implement some fiscal spending, to offset the impact of the upcoming Brexit law.

In the US, President Trump will likely struggle to get the required bipartisan support for more spending in an election year. And finally, in China, despite repeated rumours of a stimulus package and in the face of slowing domestic growth, the government has generally stuck to its objective of deleveraging the economy and accepting a lower growth rate – even though it may implement a number of micro fiscal measures as well as credit easing to cushion the blow, as discussed at Chinas Central Economic Work Conference in December.

In emerging markets, a few countries will pursue fiscal stimulus in 2020, following the growth slowdown of 2019. One key example is Turkey (see page 7). However, in most of the emerging world, monetary policy has more space compared to developed markets, and economic growth rates are generally higher, meaning the urgency for fiscal stimulus is lower.

What prevents Germany from spending?

Germany requires investments to remain globally competitive in particular in urban and digital infrastructure. For the 2020 budget, the government has allocated ~43bn to investments, some 12% of total expenditure. However, the proportion spent on education and infrastructure remains below average relative to other OECD economies.

Negative funding costs offer Germany the seemingly no-brainer remedy to finance additional investments through new debt, while simultaneously reducing interest payments. While the constitution allows debt issuance up to 0.35% of GDP per year, the self-imposed budgeting concept of black zero prevents the German government from expenditures in excess of their earnings, and therefore from accessing a potential net 6bn in 2020. Any amounts beyond this require a constitutional amendment via a two-thirds majority in both the federal parliament and council.

However, its not necessarily only a lack of public funds that impedes German investments. Scarce capacity in the construction sector paired with inefficiencies in capital deployment have caused an investment bottleneck. Case in point are the untouched 19bn accumulated from previous years budgets. Bureaucracy, lengthy tendering and approval procedures, and a lack of qualified staff delay investment allocation on a municipal level.

Against this background, increasing the budget by removing the black zero is no obvious necessity for Germany to make up for missed pent-up investment. Increasing communal efficiencies and covering the lack of specialised workforce in engineering/planning positions pose a necessary condition, before budget expansions can be considered.

Calls for a German sovereign wealth fund to circumnavigate the black zero have been met with skepticism, as critics fear the politicians influence on the asset allocation in absence of clearly-defined investment objectives. Pundits dread an overweight in social welfare spending and underweight in infrastructure projects, along the lines of the current budget. In the meantime, Germanys first sovereign wealth fund KenFo is building its track-record in light of the clear mandate to finance nuclear waste disposal.

How will the Democratic race develop in 2020?

As we wrote in The Silver Bullet | Accountable Capitalism, even though it is early in the election cycle, we believe Sen. Elizabeth Warren has a substantial chance of being nominated as the Democratic candidate.

Warren remains among the front runners into the primaries, despite a recent loss in popularity following the fourth Democratic debate in October. Recent polls reveal that a large proportion of supporters of other top Democratic candidates are also considering Warren as an alternative to their first choice, thereby confirming that she appeals to wide range of Democratic voters.

We believe this places her in a strong position to gain supporters in the eventual case of a contender dropping out of the race.

That said, other Democratic candidates could receive a boost in support over the coming months. First, the primaries and caucuses will commence in February. These events will be critical for less popular candidates such as Buttigieg, who can gain momentum and popularity in the early stages of the race. According to the most recent polls, he is head to head with Sanders and Biden in the critical Iowa caucus, which is seen as a strong indicator of how candidates will do going forward, and leads in New Hampshire, with 18% of the votes in both states.

Secondly, should an impeachment hearing in the Senate commence, this could potentially support Biden over other democratic candidates who would be unable to campaign for at least a month as their presence would be required in Washington.

Finally, Mayor Bloomberg, who announced his Democratic presidential bid only on the 24th of November, could gain considerable momentum given his popularity, considerable financial backing and fundraising power. After only the first week of his 2020 campaign Bloomberg invested $57 million in TV advertising.

What are the implications of recent elections for UK assets?

We think that the recent recovery of UK assets into the elections will fade.

On December 12th, UK elections saw a stronger-than-expected victory of the Conservative party. The vote share topped the range predicted by most polls and the Tories now enjoy a solid majority in Parliament. As a result, Brexit legislation passed by Boris Johnson in October gains strong political legitimacy, and the UK government will likely push hard to finalise the deal by the end of January.

Into the elections, UK assets have gained. The Sterling was up almost 10% against the US dollar from mid-October to just after the election results. On the elections result, both the pound and UK equities bounced significantly. The recent price action reflects a decrease in uncertainty – yet the UK economy isnt out of the woods.

First, the deal struck between UK and EU in October found an agreement for the Irish backstop and the timing of exit, but details on the new goods and services trading arrangements still need to be discussed. As the Tories are now politically stronger, chances of more standoffs with EU are now higher, as it is the tail risk of a hard or no deal Brexit, though the latter probably remains small.

Second, businesses may have already voted to leave – with their own feet. Firms relocating or moving workers out of the UK have shown no signs of reverting. According to a poll by IOD, a third of UK firms are considering relocation out of the UK or have already taken action. As a result, consumer balance sheets appear stretched, with real wages stagnant and rising household debt. House prices are stagnating too, with plenty of inventory for sale.

We have been short UK consumer-focused businesses this year and remain cautious in this sector in 2020.

Does credit divergence continue in 2020?

Since the start of QE in 2009, the ups and downs in credit markets have been driven by central banks, while strong and weak credits generally moved in tandem. From early 2016 to mid-2018, for example, re-accelerating growth and monetary easing boosted demand for low rated cyclical firms, and the spread between triple-C, single-B and BB fell to historical lows. In other words, credit dispersion fell.

Over the past year, however, credit dispersion has increased despite a general fall in credit spreads: for the first time in the past decade, central bank liquidity is no longer lifting all boats.

With the potential of trade tensions still looming and faltering growth, over-leveraged companies with weak business models have fallen into bankruptcy, most notably Thomas Cook in the UK – as well as sovereigns, like Argentina or Lebanon.

We think credit dispersion will continue in 2020, on lacklustre growth, ongoing geopolitical uncertainty and domestic volatility due to US elections.

Can investors profit in credit when spreads are tight?

We think so. In 2019, we had positioned the portfolio to profit from an increase in dispersion, through shorting zombie companies which are over-levered companies with out-dated business models, like Pizza Express, Thomas Cook and CMA, while being long survivor companies which are cash-flow positive businesses including, Wind Hellas, Matalan and select AT1s.

We think credit markets in 2020 will continue to be split between the zombie and survivor companies. We position our portfolio to be long these survivor companies, while seeking alpha opportunities from shorting potential new zombies or being long new survivors.

We separate the zombie companies from the survivors through a three-part process: we identify zombies as those with weak business fundamentals, in structurally weak sectors and subject to rising political risks. For weak business fundamentals, we focus on companies which are cash flow negative and will likely remain so for another 2 years, with leverage close to enterprise value multiples. These are companies in which investors will likely demand a plan for deleveraging either through asset sales or a capital raise. These plans will be more challenging for those companies in structurally weak sectors, our second criteria, like retail, energy or autos. Finally, our third criteria, political risks will play an increasingly important role in credit selection going forward. We think investors will be more focused on ESG selection, which will hurt sectors like commodity-producers and retailers. In addition, political campaigns could call for reform in certain sectors, like US healthcare/ pharmacy where drug prices are likely to be under increasing pressure from both Democrats and Republicans in 2020

Will the US and China reach a deal before elections?

In our view, the latest developments are positive, but a long-lasting deal is still far away.

During the past week, the US administration surprised markets by agreeing to a phase-one deal with China. The US government will not implement the new tariffs scheduled for December 15, and the tariffs introduced in September 2019 will be cut in half. China should continue to increase US products imports in exchange. While this is a positive sign, we think the US administration has likely been forced into a quick agreement by the urgency of delivering a deal to the general public, against rising attention on impeachment proceedings.

The vast majority of tariffs remains in place, and an agreement on intellectual property is far from settled. In addition, the Trump Administration may still need trade negotiations as a tool to engineer consensus into elections. Therefore, we think noise around a comprehensive phase two deal is likely to persist into next year.

From a market perspective, this is a positive surprise since investors expected a delay of new tariffs but no rollback of the old ones. Equity and higher-yielding credits have space to perform more into 2020 as positioning in risky assets is not long, and a phase-one deal reduces negative near-term risks.

Still, a risk rally will hardly be sustained in our view: the broad status of US-China relations remains uncertain, global growth stays tepid, and US elections represents an under-priced risk for 2020.

Will China stimulate its economy as it has during prior downturns?

China continues to walk a thin line between stabilising a slowing economy and containing the build-up of financial risks. We expect the PBoC to continue easing monetary policy modestly, though it is constrained somewhat by rising inflation driven by food prices. The central government appears resolute in its deleveraging campaign launched in 2017, having elected to not pursue large-scale fiscal stimulus measures that the market had been anticipating this year. Indeed, recent commentary suggests the central government may be willing to accept GDP growth below 6% for 2020 and thereafter as it seeks to put its growth trajectory on a more sustainable footing. However, the governments hand may be forced in response to financial sector instability amid slowing growth, as noted during Chinas Central Economic Work Conference this month.

For example, in May regulators seized Baoshang Bank, one of 4,000 regional banks in China which in aggregate hold 25% of system assets and typically have weak funding franchises. Regulators imposed losses on its large interbank creditors for the first time, in an attempt to instil discipline into a market that operates with the presumption of state guarantees. By June, there were reports of significant stress in the interbank market. In response regulators held two emergency meetings where state-owned banks were compelled to continue lending to stabilise the market.

With the US-China trade war likely to continue exerting downward pressure on economic growth, but a base level of economic momentum required to maintain financial stability, we believe the CCP will gradually enact a more accommodative stance toward the infrastructure and property sectors, both of which have historically served as vehicles for economic stimulus and are seeing initial signs of policy easing.

Where are the weak spots in emerging markets?

Emerging market debt strongly benefited from the re-pricing in global rates. The rally in US duration helped hard currency, and dovish EM central banks supported local currency bonds in 2019.

In this context, more emerging markets ended the year overvalued than cheap. The EM hard currency benchmark is now close to historical tights.

We believe there are at least three liquid sovereigns investors have been too complacent about: Turkey, South Africa and Brazil. Just back from a trip in Turkey, our observation is that the governments urgency to stimulate the economy again is higher than perceived by the market. For 2019, the Treasury is looking to turn the recession of this year into 5% GDP growth. To achieve such a quick change, the government is pushing hard on credit stimulus, via new incentives to banks linked to credit growth. A fiscal expansion is looming for next year, and financial conditions are very easy post the 10% cumulative cuts of 2019. On top of that, the central bank is de facto depleting reserves due to shadow interventions via local banks, and more US sanctions (on the S-400 issue this time) could hit the country in the first quarter.

Turkey experienced a large adjustment over the past 18 months. Since August 2018, the current account fully closed (from a 6% deficit), economic and credit growth turned negative, and inflation and interest rates collapsed. A fully-fledged macro blow-up is thus less likely this time, as stimulus hits less heated initial conditions. Still, Turkish assets rallied this year, especially local rates and hard currency debt. Both the cost of CDS protection and the implied lira volatility are at the lows reached before the stress in summer 2018, suggesting vulnerabilities to bad news. Episodes of stress during the year are thus highly likely, in our view.

In South Africa, 2019 marked a strong deterioration in public finances. The slowdown in growth affected government revenues and cash injections to government-owned utilities added to the bill. The medium-term budget, published in late October, projected an almost 7% budget deficit for the next fiscal year, vs 4.5% projected six months ago. With such sustained deficits, debt/GDP could go beyond 75% over the next three years, from just 55% currently.

A fiscal consolidation next year seems unlikely, as many factors behind the recent worsening are structural. If anything, a continuation of the low growth environment could further exacerbate the problem, considering the high beta of the country to global growth. Local rates have lagged the global duration rally for good reasons, but could continue to underperform, as the government will need to issue more local debt to finance large deficits. Rand levels are middle of the historical range from a real trade-weighted perspective, while the cost of CDS protections is very low. As such, more fiscal stress next year is likely and not fully priced by markets.

Brazil has been a big beneficiary of investment flows in 2019, and one where inflows started earlier than elsewhere. As the new right-wing government proved market-friendly in early October 2018, markets started re-assessing the country story more positively. In 2019, the government was finally able to pass the well-anticipated pension reform, and BCB embarked on a deep cutting cycle. As a result, rates have tightened massively.

Into 2020, risks for Brazil are skewed on the downside. Rates are at historical tights vs inflation, reducing the attractiveness of holding the currency. GDP growth has slowed down for the first half of the year, and positive catalysts lack, as good news on the politics and the fiscal outlook largely played out in the past 12 months. In 2020, a negative turn in EM sentiment would leave Brazil fragile, given the less attractive carry and the still high level of public debt. The currency already started moving, and central bank reserves are high enough to keep FX relatively stable. Local duration and EXD are very tight and remain more vulnerable.

What countries took advantage of low rates to tackle longer-term issues?

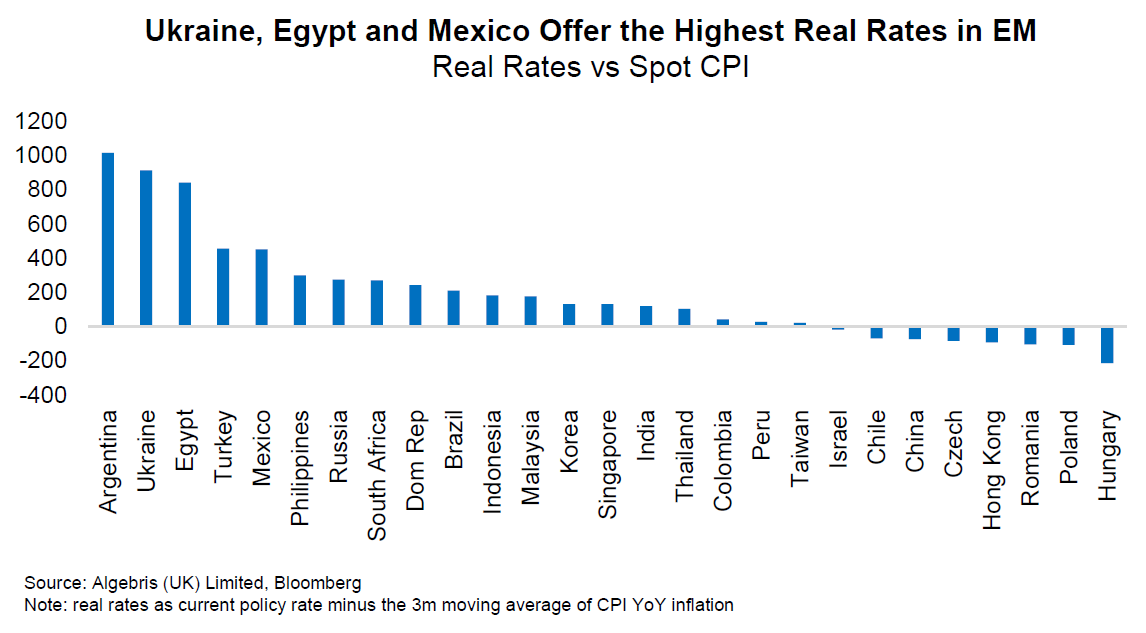

Low rates usually push countries to relax lending standards and fiscal discipline, creating unwarranted imbalances. There are a few cases though where low financing costs help countries channel funds the right way, ultimately promoting a healthier structure. In 2019, this has been the case in Mexico, Egypt, Ukraine and Greece.

In Mexico, the year started with weak currency and high rates as the market perceived the new government as populist. In fact, AMLO has proved to be substantially more market-friendly than feared, implementing a prudent fiscal policy and avoiding escalations with the US.

While Fed cuts eventually pushed Banxico into easing, the central bank has been cautious, so that Mexico is now the only liquid emerging markets with substantially high real rates and more room for cutting. A ratification of the new trade deal with the US (USMCA) in the next few months provides a positive catalyst for the currency too. We remain constructive on duration, the peso and state-owned Pemex, which trades wide to the sovereign despite being at all effects a government liability.

Ukraine and Egypt remain two structural transformation stories where low rates contributed to a healthy opening of capital markets. In both cases, IMF support helped a wave of reforms and a re-pricing of external debt between 2016 and 2018. In 2019, low global rates helped deep cuts and a liberalisation of local markets, where foreign participation was non-existent to begin with. The two countries have cut policy rates, respectively, by 250bp and 450bp, and are signalling a similar amount for next year. In both cases, local bonds will need to reprice further as the curve is still not pricing enough.

Greece enters this category too. Post July elections, the government has taken steps towards an ambitious cut of corporate taxes, an asset protection scheme to reduce NPLs, and a deep labour market reform. This marks a seminal change for the country, after having been a bad example within the European periphery for almost a decade. We maintain a positive attitude on the country but market conviction is lower as Greece spreads turned very tight this year. Market-driven sell-offs would be an opportunity to add.

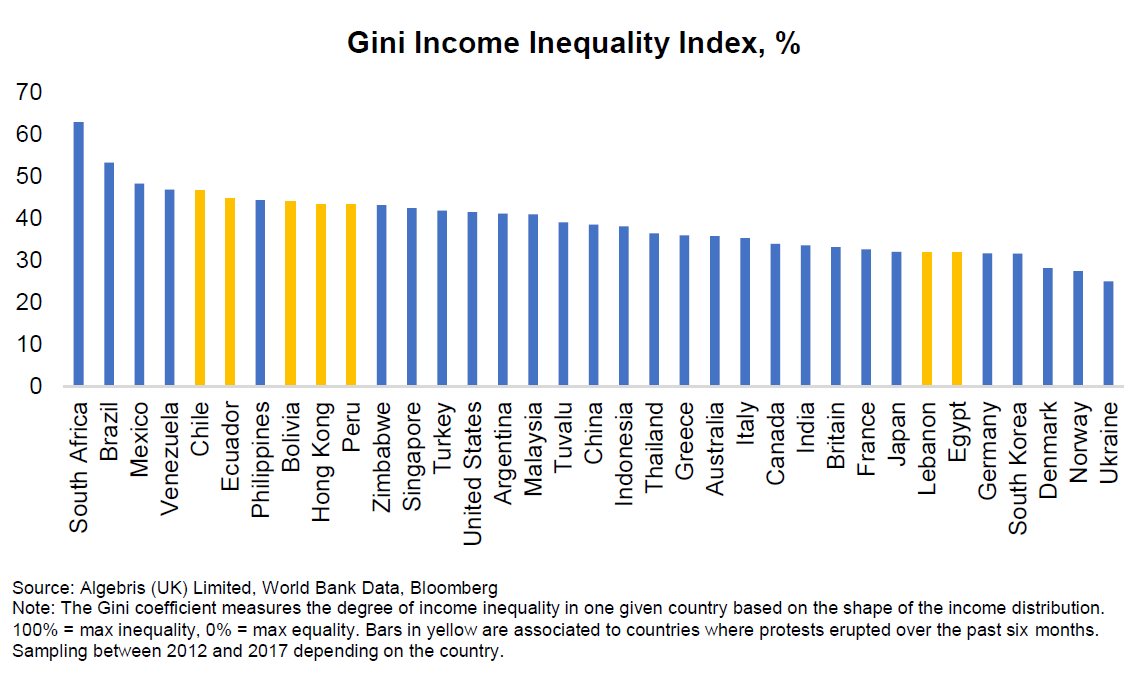

Will the recent wave of global protests affect markets in a more meaningful way?

The past few months have seen a strong pick-up in popular protests across the globe. While the first ones started in Asia / Middle-East (Hong Kong, Egypt, Lebanon), rallies are intensifying mostly in Latin America (Chile, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru).

The trait dunion of the protests is inequality. As global growth struggles, the bottom 50% in developing countries suffer more. The tolerance for restrictive political regimes or austerity-imposing fiscal programs has thus become very limited. For markets, this means additional downside risks from sluggish growth. Countries with weak growth dynamics and high inequality are at risk of political instability. South Africa, with almost 30% unemployment, large fiscal burdens and slowing growth, is a good candidate to be next in line.

Short-term, Latin America deserves some particular attention. The region has historically been unstable, and protests in the above-mentioned countries add to populist governments in Argentina and Venezuela. The political climate is definitely more favourable in the two main economies, Brazil and Mexico, but risks for some short-term contagion persist. The Brazilian real, for example, has followed the Chilean and Colombian peso weaker in the past month despite little local developments.

Conclusions: Active Management for the Daring Decade

In 2016 and 2017, we positioned our macro credit fund to benefit from excessive fears of recession risks and of Eurozone instability. We bought Greek debt, emerging market and high yield cyclicals with a final focus on the Eurozone, which remained unloved by investors at the time. In 2018, we de-risked our portfolio. However, as markets started falling due to rising political risks, we held on to assets which we estimated to be money good. We learnt the lesson that central banks can drive markets and liquidity with it, regardless of fundamentals.

In 2019 we positioned for a turn in central banks hawkishness, which we estimated as a policy mistake, back to easing. We also worried that despite another tide of central bank liquidity, many borrowers had become weak. For the first time in the QE decade, low rates and asset purchases did not lift all boats. Several credits defaulted or fell into distress this year – Argentina, Lebanon, Thomas Cook to name a few among our shorts – with record-high dispersion in high yield and emerging markets, despite low spreads overall.

We believe policymakers and voters are increasingly done with the kick-the-can decade, where monetary easing pushed the economy forward but structural issues remained untouched. Governments will look for more radical solutions to solve long-standing economic issues like rising inequality and low social mobility, stagnant productivity and real wages, and climate change. Not all these solutions will be market friendly.

Fixed income investors face an environment where limited assets offer positive real yields, and where these real returns come with substantial risks.

This represents a difficult environment for investors in fixed income beta, but it is a fertile ground for alpha, which this year made up around half or more of our returns. Going forward, we think our long-short approach and our macro-micro investment process will be able to capture more alpha opportunities.

We would like to thank you for trusting us with your capital, and look forward to investing together in the next decade.

For more information about Algebris and its products, or to be added to our distribution lists, please contact Investor Relations at algebrisIR@algebris.com. Visit Algebris Insights for past commentaries.

This document is issued by Algebris Investments. It is for private circulation only. The information contained in this document is strictly confidential and is only for the use of the person to whom it is sent. The information contained herein may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any recipient for any purpose without the prior written consent of Algebris Investments.

The information and opinions contained in this document are for background purposes only, do not purport to be full or complete and do not constitute investment advice. Algebris Investments is not hereby arranging or agreeing to arrange any transaction in any investment whatsoever or otherwise undertaking any activity requiring authorisation under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. This document does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of an offer to subscribe or purchase, any investment nor shall it or the fact of its distribution form the basis of, or be relied on in connection with, any contract therefore.

No reliance may be placed for any purpose on the information and opinions contained in this document or their accuracy or completeness. No representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in this document by any of Algebris Investments, its members, employees or affiliates and no liability is accepted by such persons for the accuracy or completeness of any such information or opinions.

This document is being communicated by Algebris Investments only to persons to whom it may lawfully be issued under The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 including persons who are authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 of the United Kingdom (the “Act”), certain persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, high net worth companies, high net worth unincorporated associations and partnerships, trustees of high value trusts and persons who qualify as certified sophisticated investors. This document is exempt from the prohibition in Section 21 of the Act on the communication by persons not authorised under the Act of invitations or inducements to engage in investment activity on the ground that it is being issued only to such types of person. This is a marketing document.

The distribution of this document may be restricted in certain jurisdictions. The above information is for general guidance only, and it is the responsibility of any person or persons in possession of this document to inform themselves of, and to observe, all applicable laws and regulations of any relevant jurisdiction. This document is suitable for professional investors only. Algebris Group comprises Algebris (UK) Limited, Algebris Investments (Ireland) Limited, Algebris Investments (US) Inc. Algebris Investments (Asia) Limited, Algebris Investments K.K. and other non-regulated companies such as special purposes vehicles, general partner entities and holding companies.

© Algebris Investments. Algebris Investments is the trading name for the Algebris Group.